A coup too far: Why Benin's rebel soldiers failed where others in the region succeeded

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesHad last week's coup attempt in Benin been successful, it would have become the ninth to take hold in the region in the last five years alone.

Just a few days after soldiers took power in Guinea-Bissau while a presidential election vote count was still under way, leaders of the West African grouping Ecowas rapidly concluded that Sunday's attempted overthrow of Benin's President Patrice Talon was one destabilising step too far.

In support of his government, Nigerian warplanes bombarded mutinous soldiers at the national TV and radio station and a military base near the airport in Cotonou, the largest city.

Ecowas also announced the deployment of ground troops from Ghana, Nigeria, Ivory Coast and Sierra Leone to reinforce the defence of constitutional order.

This is a region that has been shaken by repeated coups since 2020, and which little more than 10 months ago saw the putschist regimes in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger completely withdraw their countries from Ecowas - the Economic Community of West African States - of which they had all been founding participants 50 years ago.

So, faced with the prospect that yet another civilian government might be overturned by discontented soldiers, the presidents of the remaining Ecowas member states rapidly reached the conclusion that the attempted coup in Cotonou could not be allowed to succeed.

Learning from past mistakes

Having fought off early morning putschist attacks on Talon's home and the presidency offices, loyalist forces had already reaffirmed government control across the city, locking down the main central administrative district.

But it was proving hard to break down the last-ditch resistance of rebel troops who had shown they were ready to use lethal force without regard for civilians.

In response, Nigeria's President Bola Tinubu, Benin's eastern neighbour and much the largest military power in the region, authorised air strikes, while Ecowas leaders decided to despatch ground troops the same day.

Among those sending forces is Ghana's President John Mahama, who leads a resilient democracy but has made friendly diplomatic overtures to the Sahelian military regimes.

In acting so quickly, Ecowas has perhaps learned a lesson from its misjudged response to the 2023 coup in Niger.

On that occasion it was not practically organised to intervene militarily in the hours after the elected head of state, Mohamed Bazoum, had been detained by coup leaders – the only moment, perhaps, when a rapid commando raid to rescue him and secure key buildings might have had any chance of success.

By the time the bloc had threatened intervention and begun to plan it, the chance had gone: the new junta had consolidated control over the Nigérien army and mobilised popular opinion in its support.

Faced with the prospect of intervention becoming full-scale war, and under strong domestic popular pressure to avoid any such bloodbath, Ecowas leaders backed off - opting to rely on sanctions. And when those also proved counter-productive, they settled for the diplomatic path alone.

This time around, in Benin, the situation was quite different: Talon was still in full control, even if some would-be putschists were still resisting. So he, as the internationally recognised president, could legitimately request support from fellow member countries in the regional bloc.

And this seems to have had popular support in Cotonou.

Many Béninois citizens do have grievances against the current government, notably over the exclusion of Les Démocrates, the main opposition party, from the forthcoming presidential election.

But there is a strong culture in Benin of trying to achieve change through political and civil society action, rather than force.

Béninois are rightly proud of their country's role as the pioneering instigator of the wave of peaceful mass protest and democratisation that swept across francophone Africa in the early 1990s.

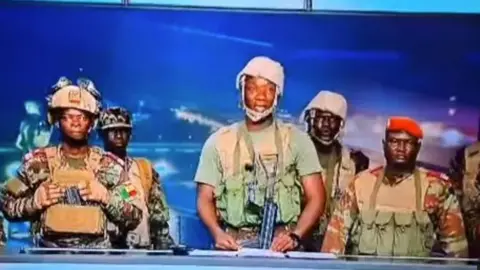

BTV

BTVWhile the complaints against Talon aired by the would-be putschists during their brief appearance on national television are widely shared, there has been absolutely no sign of any popular support for their attempt to get rid of the government by force.

So Benin represented a particularly favourable context for a forceful Ecowas intervention in defence of constitutional civilian rule.

Indeed, if anything, the coup-plotters are likely to become the target of growing public anger as news of casualties circulates. At least one civilian – the wife of Talon's key military adviser – was killed.

In recent days two top military officials abducted during Sunday's failed coup attempt in Benin have been rescued, but security forces are still searching for the coup leader Lt Col Pascal Tigri and other plotters.

Simmering grievances

This was just the latest in a string of coup attempts across the region, though most of the others have in fact succeeded.

They have all occurred in a context of fragility and pressure across West Africa at a time of Islamist violence across the Sahel, now spreading into the northern regions of many coastal countries.

There is disenchantment with traditional political elites. Even where economies are growing well, a desperate shortage of jobs and viable livelihoods, for the region's rapidly growing young population.

However, while the regional context is widely shared, the driving factors for the coups are often local - specific to each country.

The lack of popular support for the Cotonou putschists stands in stark contrast to the mood on the streets of Conakry, the Guinean capital, in September 2021, when the commander of special forces, Col Mamady Doumbouya led the overthrow of then-President Alpha Condé.

Like Talon, Condé had first been democratically elected but later secured re-election in questionable conditions, and presided over a significant erosion of political freedoms. Yet in Guinea, Condé had presided over the violent abuse on a far greater scale than in Benin.

In addition, Condé had then strong-armed his way to a third term aged 83. Whereas the 67-year-old Talon has promised to step down next April, albeit having adjusted the electoral rules to almost guarantee an easy victory for his chosen successor, Finance Minister Romuald Wadagni.

Another key difference is Condé's deeply disappointing economic track record, whereas Talon has presided over strong growth and improving services.

Go to BBCAfrica.com for more news from the African continent.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, on Facebook at BBC Africa or on Instagram at bbcafrica