The serenity of a late afternoon on the Moei River that divides Thailand from Myanmar is broken by three thunderous explosions. The ethnic Karen families bathing and playing in the water make a panicked dash for the river bank, as a plume of dark smoke rises from the trees behind them.

The conflict ignited by the Myanmar military's coup nearly five years ago has come back to the border.

But the fighting this time is linked to the scam compounds, run by Chinese crime syndicates, which have proliferated in Karen State in the past two years.

We are working to completely eradicate online scam activities from their roots, the Myanmar junta's spokesman Gen Zaw Min Tun said.

But there are good reasons for scepticism about the military's claims. Now, for the first time, Myanmar's long civil war and its scam crisis are entwined.

After losing control of large areas of the country to insurgent groups, this year the military junta has counter-attacked, reinforced by new conscripts and new equipment like drones supplied by Russia and China. In Karen State, it has driven back the forces of its main opponent, the Karen National Union, which it has been fighting for eight decades, and which has been one of the staunchest opponents of the coup.

Suddenly, at the end of October, the army stormed KK Park, one of the largest and most notorious scam compounds in Karen State, driving out thousands of foreigners who had been running online fraud schemes there, some voluntarily, some after being tricked or trafficked and forced to work. The army posted videos of soldiers confiscating thousands of mobile phones, computers, and satellite dishes from Elon Musk's Starlink service. They began demolishing buildings with explosives.

This was a striking change of heart. For years, Myanmar's military rulers turned a blind eye to the multi-billion dollar scam business expanding rapidly along its border with Thailand. Local warlords allied to the military have been the principal protectors and business partners of the Chinese scam bosses, and have become very rich. Some of that money went into the coffers of the ruling generals. The junta has tried to blame the KNU for the scams, but there is no basis for this; unlike the other armed Karen groups, the KNU has kept its distance from the business.

The darkest side of the industry is felt in South East Asia, where these online fraud schemes are linked to human trafficking, money laundering, and extensive human rights abuses.

There is growing international concern, and co-ordination between law enforcement agencies, to try to combat this scourge. The US has set up a multi-agency anti-scam task force. China, one of the Myanmar military junta's closest allies, has been pressing it to do more for years because thousands of Chinese citizens have fallen victim both to online fraud and to being trafficked and held for ransom in the compounds.

From the reports in Myanmar state media showcasing the military's actions in KK Park, it would appear that this pressure is finally working.

And yet its demolitions in KK Park, while spectacular, do not appear to have destroyed the infrastructure for scamming there. And the military operations have focused only on this compound; there are dozens of others. It did raid the scam city of Shwe Kokko, but only entered a few buildings, and to date has demolished only one.

Thousands of foreign scam workers have left KK Park and Shwe Kokko and made their way across the Moei River to Thailand. Many others have scattered to different locations, although transport is difficult and expensive. The main scam bosses are presumed to have taken their businesses to more remote, less visible parts of Myanmar further south on the border.

But in a town called Minletpan, one group of scam workers was trapped last month in two compounds, known as Shunda and Baoili. These have been built right by the river just in the past two years. They are in an area controlled by the DKBA, one of the militias allied to the military junta.

The KNU announced that it wanted to set an example by inviting journalists and international law enforcement agencies to see the captured compounds. It published photographs and documents to expose how the scam business works, rather than destroying the evidence as the military has done in KK Park.

But aside from a handful of journalists, the international interest in its prize never materialised, and the junta's forces began shelling the area to try to retake the compounds. Many of the remaining scam workers have now fled elsewhere in Myanmar, though a few hundred remain camped under flimsy tarpaulins on the river bank, along with hundreds of local people, all hoping to avoid the artillery exchanges.

All this drama is down to one thing: the junta's much-criticised plan to hold an election later this month. The military regime is loathed by most of Myanmar's people, and is treated as a pariah internationally. The generals are looking for an off-ramp which will buy them a semblance of legitimacy, and win over some of their many opponents. They have chosen an election, but one in which the main opposition groups either cannot or will not take part, and where much of the country is in too much turmoil for voting to take place at all.

Whatever the future of well-known scam complexes like KK Park and Shwe Kokko – and it is too soon to judge whether they really are being shut down – the scam business is still thriving in Myanmar.

The conflict ignited by the Myanmar military's coup nearly five years ago has come back to the border.

But the fighting this time is linked to the scam compounds, run by Chinese crime syndicates, which have proliferated in Karen State in the past two years.

We are working to completely eradicate online scam activities from their roots, the Myanmar junta's spokesman Gen Zaw Min Tun said.

But there are good reasons for scepticism about the military's claims. Now, for the first time, Myanmar's long civil war and its scam crisis are entwined.

After losing control of large areas of the country to insurgent groups, this year the military junta has counter-attacked, reinforced by new conscripts and new equipment like drones supplied by Russia and China. In Karen State, it has driven back the forces of its main opponent, the Karen National Union, which it has been fighting for eight decades, and which has been one of the staunchest opponents of the coup.

Suddenly, at the end of October, the army stormed KK Park, one of the largest and most notorious scam compounds in Karen State, driving out thousands of foreigners who had been running online fraud schemes there, some voluntarily, some after being tricked or trafficked and forced to work. The army posted videos of soldiers confiscating thousands of mobile phones, computers, and satellite dishes from Elon Musk's Starlink service. They began demolishing buildings with explosives.

This was a striking change of heart. For years, Myanmar's military rulers turned a blind eye to the multi-billion dollar scam business expanding rapidly along its border with Thailand. Local warlords allied to the military have been the principal protectors and business partners of the Chinese scam bosses, and have become very rich. Some of that money went into the coffers of the ruling generals. The junta has tried to blame the KNU for the scams, but there is no basis for this; unlike the other armed Karen groups, the KNU has kept its distance from the business.

The darkest side of the industry is felt in South East Asia, where these online fraud schemes are linked to human trafficking, money laundering, and extensive human rights abuses.

There is growing international concern, and co-ordination between law enforcement agencies, to try to combat this scourge. The US has set up a multi-agency anti-scam task force. China, one of the Myanmar military junta's closest allies, has been pressing it to do more for years because thousands of Chinese citizens have fallen victim both to online fraud and to being trafficked and held for ransom in the compounds.

From the reports in Myanmar state media showcasing the military's actions in KK Park, it would appear that this pressure is finally working.

And yet its demolitions in KK Park, while spectacular, do not appear to have destroyed the infrastructure for scamming there. And the military operations have focused only on this compound; there are dozens of others. It did raid the scam city of Shwe Kokko, but only entered a few buildings, and to date has demolished only one.

Thousands of foreign scam workers have left KK Park and Shwe Kokko and made their way across the Moei River to Thailand. Many others have scattered to different locations, although transport is difficult and expensive. The main scam bosses are presumed to have taken their businesses to more remote, less visible parts of Myanmar further south on the border.

But in a town called Minletpan, one group of scam workers was trapped last month in two compounds, known as Shunda and Baoili. These have been built right by the river just in the past two years. They are in an area controlled by the DKBA, one of the militias allied to the military junta.

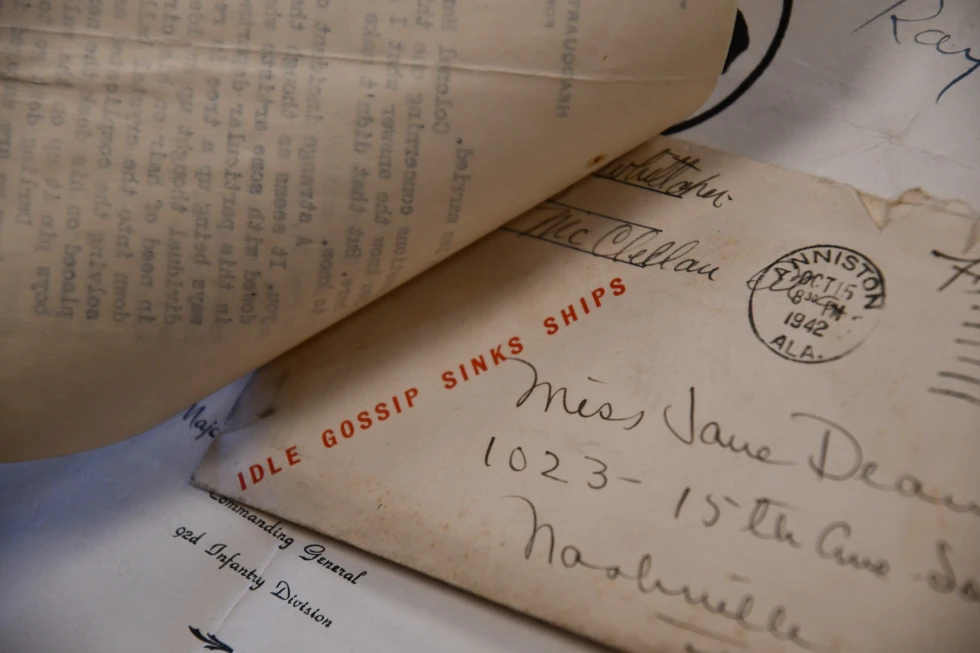

The KNU announced that it wanted to set an example by inviting journalists and international law enforcement agencies to see the captured compounds. It published photographs and documents to expose how the scam business works, rather than destroying the evidence as the military has done in KK Park.

But aside from a handful of journalists, the international interest in its prize never materialised, and the junta's forces began shelling the area to try to retake the compounds. Many of the remaining scam workers have now fled elsewhere in Myanmar, though a few hundred remain camped under flimsy tarpaulins on the river bank, along with hundreds of local people, all hoping to avoid the artillery exchanges.

All this drama is down to one thing: the junta's much-criticised plan to hold an election later this month. The military regime is loathed by most of Myanmar's people, and is treated as a pariah internationally. The generals are looking for an off-ramp which will buy them a semblance of legitimacy, and win over some of their many opponents. They have chosen an election, but one in which the main opposition groups either cannot or will not take part, and where much of the country is in too much turmoil for voting to take place at all.

Whatever the future of well-known scam complexes like KK Park and Shwe Kokko – and it is too soon to judge whether they really are being shut down – the scam business is still thriving in Myanmar.