How does an authoritarian regime die? As Ernest Hemingway famously said about going broke – gradually then suddenly.

The protesters in Iran and their supporters abroad were hoping that the Islamic regime in Tehran was at the suddenly stage. The signs are, if it is dying, it is still at gradual.

The last two weeks of unrest add up to a big crisis for the regime. Iranian anger and frustration have exploded into the streets before, but the latest explosion comes on top of all the military blows inflicted on Iran in the last two years by the US and Israel.

But more significant for hard-pressed Iranians struggling to feed their families has been the impact of sanctions.

In the latest blow for the Iranian economy, all the UN sanctions lifted under the now dead 2015 nuclear deal were reimposed by the UK, Germany, and France in September. In 2025 food price inflation was more than 70%. The currency, the rial, reached a record low in December.

While the Iranian regime is under huge pressure, the evidence is that it's not about to die. Crucially, the security forces remain loyal. Since the Islamic revolution in 1979 the Iranian authorities have spent time and money creating an elaborate and ruthless network of coercion and repression.

In the last two weeks, the regime's forces obeyed orders to shoot their fellow citizens in the streets. The result is that the demonstrations of the last few weeks have ended - as far as we can tell in a country whose rulers continue to impose a communications blackout.

At the forefront of the suppression of protest is the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), the most important single organization in the country. It has specific tasks defending the ideology and system of government of the Islamic revolution of 1979, answering directly to the supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. The IRGC is estimated to have something like 150,000 men under arms, operating as a parallel force to Iran's conventional armed military. It is also a major player in the Iranian economy.

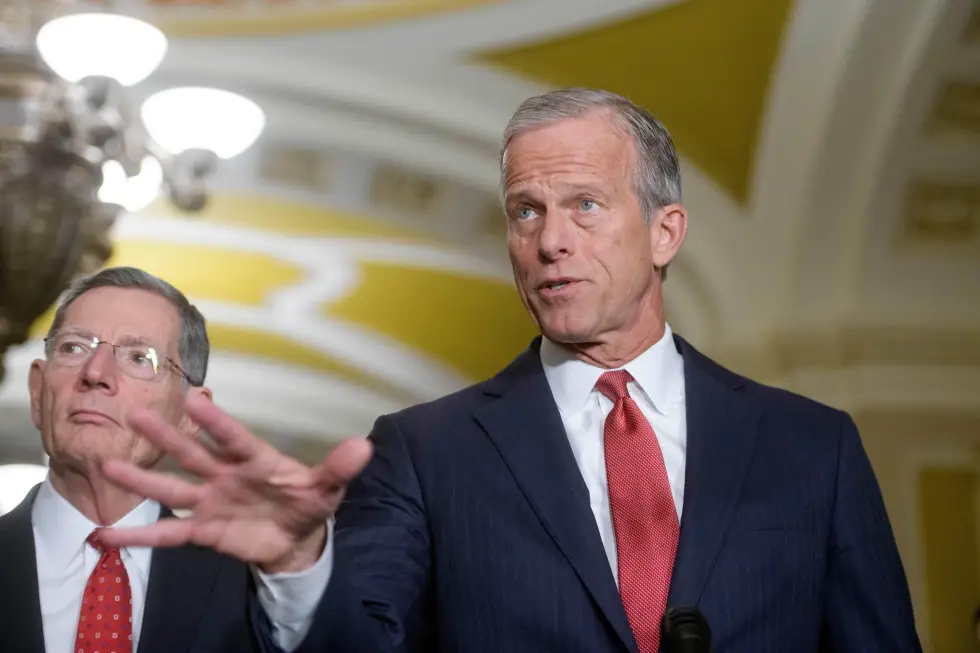

The seeming resilience of the internal security forces does not mean that the supreme leader or his lieutenants can or will relax. US President Donald Trump is still threatening to take action. The millions of Iranians who want the fall of the regime must be seething with resentment and anger.

In Tehran, the government and the supreme leader appear to be looking for ways to release some of the pressure they are facing. Bellicose official rhetoric is mixed with an offer to resume negotiations with the US.

One lesson that might worry the clerics and military men in Tehran comes from their erstwhile ally, former President Bashar al-Assad of Syria. He seemed to have won his war and was being slowly rehabilitated by Saudi Arabia and the Arab League when he emerged faced with a well-organized rebel offensive. Both Russia and Iran, his two most important allies, were neither willing nor capable of saving him. Within days, Assad and his family were flying into exile in Moscow.

An authoritarian regime decays gradually, then suddenly. The Iranian regime may yet face such a day—just not yet. Opposition leaders are hoping for more pressure at home and abroad, hoping to leverage an eventual shift from gradual decline to sudden collapse.