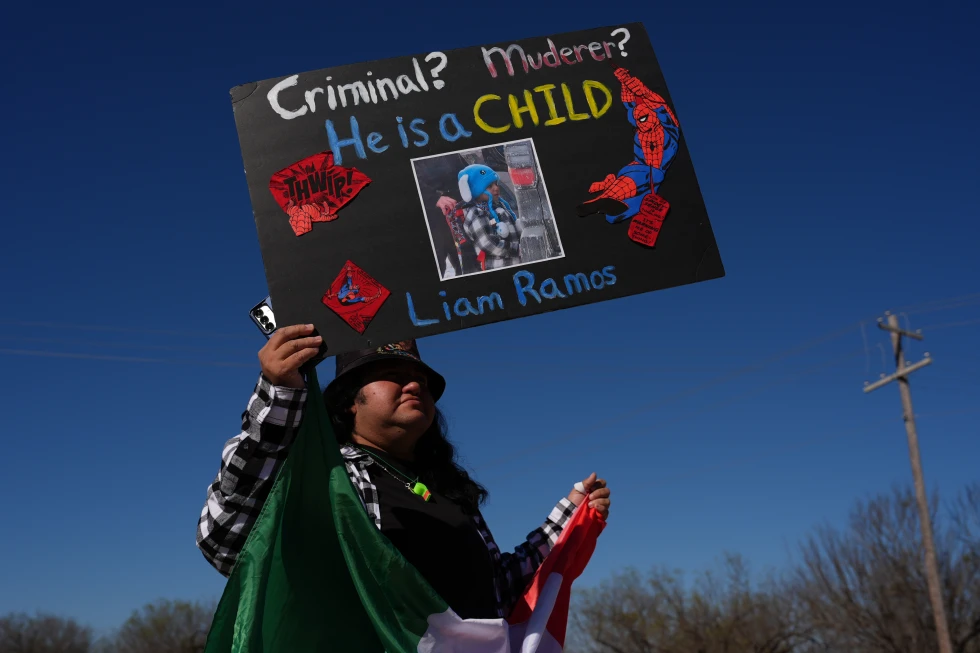

The Australian state of Queensland has recently passed groundbreaking legislation allowing children as young as 10 to be sentenced as adults for serious crimes such as murder and serious assault. The government's stance is that these laws are a direct response to widespread public concern regarding youth crime, aiming to serve as a deterrent against young offenders.

However, this decision has faced substantial criticism from experts who argue that empirical data indicates that tougher sentencing measures do not effectively deter youth crime and may even worsen the situation. The United Nations has also condemned the reforms, highlighting their contradiction with principles surrounding children's rights and international law.

The ruling Liberal National Party (LNP), which won the state election in October, made this reform a central part of its platform, prioritizing the "rights of victims" over those of juvenile offenders. Premier David Crisafulli noted that these laws are designed for Queenslanders who have felt victimized by youth crime.

Political tension flared before the new laws were passed, with claims from both major parties that Queensland is experiencing a youth crime epidemic that necessitates a more stringent approach. However, statistics from the Australian Bureau of Statistics reveal that youth crime rates have significantly decreased in the past 14 years, reaching their lowest recorded levels in 2022.

The new legislation, often referred to by the government as "adult crime, adult time," expands the list of 13 offences for which young offenders will face more severe penalties. Notably, it imposes life sentences for murder with a minimum parole period of 20 years. Previously, individuals under 18 could typically receive a maximum of 10 years for murder, with life sentences only applicable in extreme circumstances.

In addition, the laws eliminate provisions that viewed detention as a last resort, pushing for harsher penalties even for younger offenders. This has alarmed many, including Queensland's Attorney-General Deb Frecklington, who acknowledged the impending conflict with international norms and the disproportionate impact on Indigenous children. Challenges are anticipated as detention facilities are already crowded, potentially leading to longer stays in police custody as alternatives are sought.

Anne Hollonds, Australia’s commissioner for children, labeled these changes “an international embarrassment,” asserting that the adjustments neglect critical research suggesting that early interactions with the justice system heighten the likelihood of future offenses among children. Legal experts have also warned of unintended consequences, arguing that the fear of facing severe sentences may deter children from pleading guilty and result in increased court congestion.

As the state grapples with this contentious issue, the long-term implications of the new laws remain to be seen, with many advocating for more humane approaches to juvenile justice that focus on rehabilitation rather than punishment.