In a significant shift in its approach to juvenile delinquency, Queensland's government has enacted legislation that will now hold children as young as 10 accountable for crimes with penalties similar to those faced by adults. This law covers serious offenses including murder, serious assault, and burglary, positioning itself as a response to growing public concerns about youth crime in the state.

Premier David Crisafulli emphasized that the new sentencing framework, which is being referred to as "adult crime, adult time," is designed to prioritize the rights of crime victims. He argued that the community has a right to feel safe, and the government has a responsibility to act. However, the legislation has sparked backlash from experts who contend that imposing stricter penalties does not effectively deter youth crime and may even contribute to increased recidivism.

Notably, the United Nations has raised alarms about the reform, citing violations of children's rights and international law. Despite claims of a youth crime wave, statistical data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics reveal a marked decline in youth crime rates in Queensland over the past 14 years. In fact, 2022 recorded the lowest rates in history, continuing a trend of decreasing offenses.

Under the new law, a total of 13 specific crimes will carry mandatory life sentences for minors, with non-parole periods of at least 20 years for murder convictions. This represents a significant increase from the previous maximum penalty of 10 years for similar offenses. Additionally, the reform eliminates provisions designed to treat detention as a last resort and allows courts to consider a minor's full criminal history when determining sentencing.

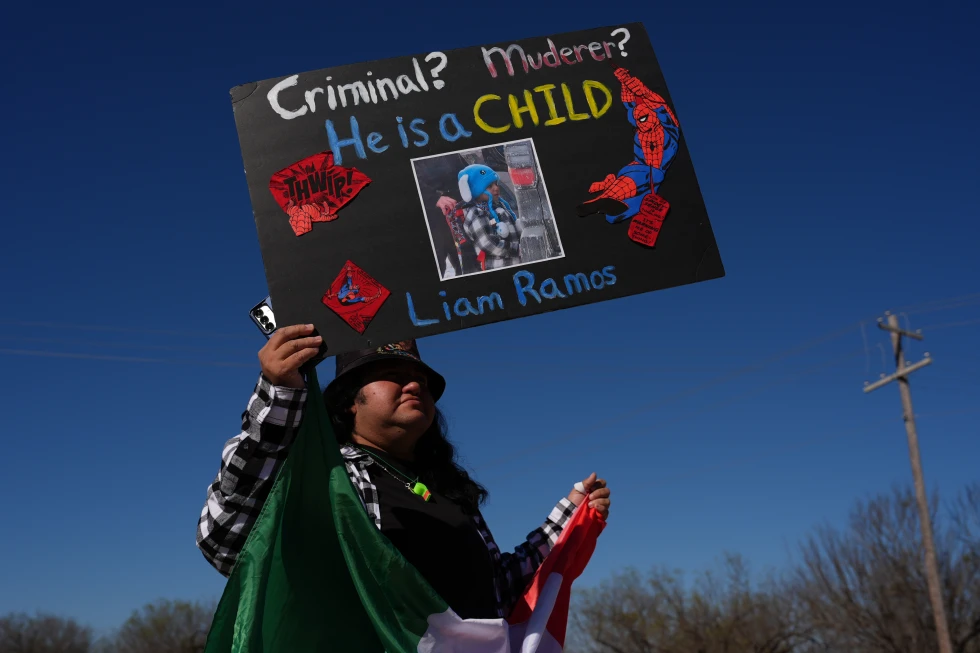

The Queensland Police Union has backed the changes, describing them as a move in the right direction. Attorney-General Deb Frecklington acknowledged potential conflicts with international standards but defended the law as essential for accountability. Concerns linger, however, about the potential impact on Indigenous children and the prospect of increasing numbers of youth being detained in police cells amid already full facilities.

Critics, including Australia's commissioner for children, Anne Hollonds, have condemned the modifications as an international embarrassment. They warn that increased contact with the judicial system at a young age could lead to more serious future offenses, marking a troubling trend in the state's approach to juvenile justice. Legal experts raised alarms during parliamentary hearings that harsher penalties could discourage guilty pleas from minors, leading to longer trial processes and consequently, more strain on the judicial system.

As Queensland's government navigates the immediate consequences of its legislative changes, it faces mounting scrutiny from advocacy groups, legal experts, and the international community regarding the long-term implications for children and society as a whole.