Japan's prime minister, Sanae Takaichi, rolled the dice on a snap election - and it paid off.

She and her Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) have the kind of decisive majority - 316 out of 465 seats - that few leaders have enjoyed recently. Rather, Japan has had a revolving door of prime ministers.

Now the question is what Takaichi does with it. Can she deliver what has eluded the Japanese economy for decades: faster growth?

Japan has a long list of problems: sluggish growth, public debt that is the largest in the world, and a working population that is both aging and shrinking.

Takaichi, some observers believe, has the chance to change this, reshaping how Japan runs what is the world's fourth-largest economy - and how the markets see it.

She will steer Japan in the right direction, says Tomohiko Taniguchi, a policy adviser and former speechwriter for late prime minister Shinzo Abe.

If successful, it will serve as a premier case study for aging societies worldwide.

Where will the money come from?

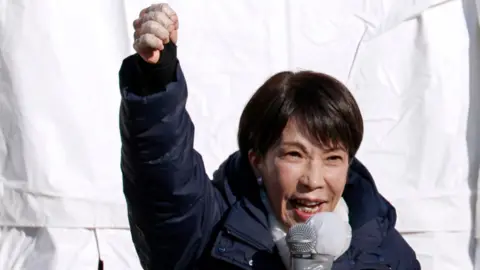

Takaichi had campaigned on the promise that she will spend more, including investment in key industries, to boost growth.

This was a pivot from her predecessors. She vowed to cut taxes so people can spend more, and said growth rather than savings was the priority.

But markets were rattled with doubt over how she would fund these plans. Her overwhelming majority seems to have assured investors - and it showed in the positive market reaction to her Sunday night win.

Investors have been placing what they call the Takaichi trade, buying Japanese shares while selling the yen and government debt. Crucially, the yen has also gone up in value - for some investors, a stronger currency is a good thing.

But it's more complicated than that.

When Takaichi came into office in October, government bond yields - effectively the interest Japan pays to borrow money - jumped.

That's a major concern for investors because of Japan's steep public debt. More spending and lower taxes - which Takaichi has been promising - means the government needs to borrow more money.

Japan's bond market is one of the largest in the world, so even small changes in Tokyo can ripple across global markets, affecting borrowing costs, investment decisions, and currencies.

Investors are also watching interest rates because the Bank of Japan is trying to move away from decades of ultra-low rates to control inflation.

The cost of rice, for example, doubled in 2025. Rising prices are a shock for a country that has become accustomed to stable or falling prices.

This was central to the message that powered Takaichi's rise: voters feel poorer and prices feel higher. After all, it was one of the issues that cost her predecessor his job.

Takaichi's proposed tax cuts may ease the pain for households in the short term.

But Keiichiro Kobayashi, professor of economics at Keio University, warns that this is a dangerous path: An increase in spending would just stimulate inflation and increase the cost of living.

Instead, he says, the government should allow the Bank of Japan to continue raising interest rates to fight inflation, while tightening government spending, which would also satisfy investors.

Because Japan is less attractive to foreign investors when interest rates are low and government spending is high, that reduces demand for the currency and weakens it.

A weaker yen pushes up the cost of imports, especially energy and food, but it can help exporters competing with cheaper Chinese goods.

It's an incredibly delicate balancing act that Takaichi cannot escape if she wants the growth she has promised.

A missing piece of the puzzle

Japan's population - and its workforce - has been shrinking for years. It is now one of the oldest societies in the world, putting immense pressure on public services such as healthcare and social care.

It is already facing acute labour shortages in construction, care work, agriculture, and hospitality. Fewer workers mean less output and, therefore, weaker growth.

Immigration could ease this strain. Official data shows the government has quietly relaxed some rules in recent years and the number of foreign workers has risen. But there are still far fewer foreign workers in Japan compared to Europe or North America.

Takaichi has signalled she is unlikely to do much to change this because immigration is hugely sensitive, especially among her conservative base.

She and her allies say Japan should instead lean on technology, automation, and higher participation by women and older workers to lift productivity.

Economists warn that may not be enough. Japan still needs more foreign workers - just as other advanced economies have long relied on them to keep their economies running.

Observers say the resistance to immigration is also part of a wider reluctance to change, which has stood in the way of innovation and reforms in the past.

What about China?

But Japan needs to change - and fast, because China has already overtaken it in scale and industrial capacity, while Vietnam and other Asian economies are catching up.

Beijing is also Tokyo's biggest trading partner. And that is important for Takaichi's plan because a rebound of domestic demand will take time - until then Japan will have to rely on trade to boost growth.

But ongoing tensions with Beijing, including a dispute over rare earth exports, have exposed Japan's vulnerability in strategic supply chains. These tensions could unsettle production in electric vehicles and defence equipment too, says Naoki Hattori, chief Japan economist at Mizuho.

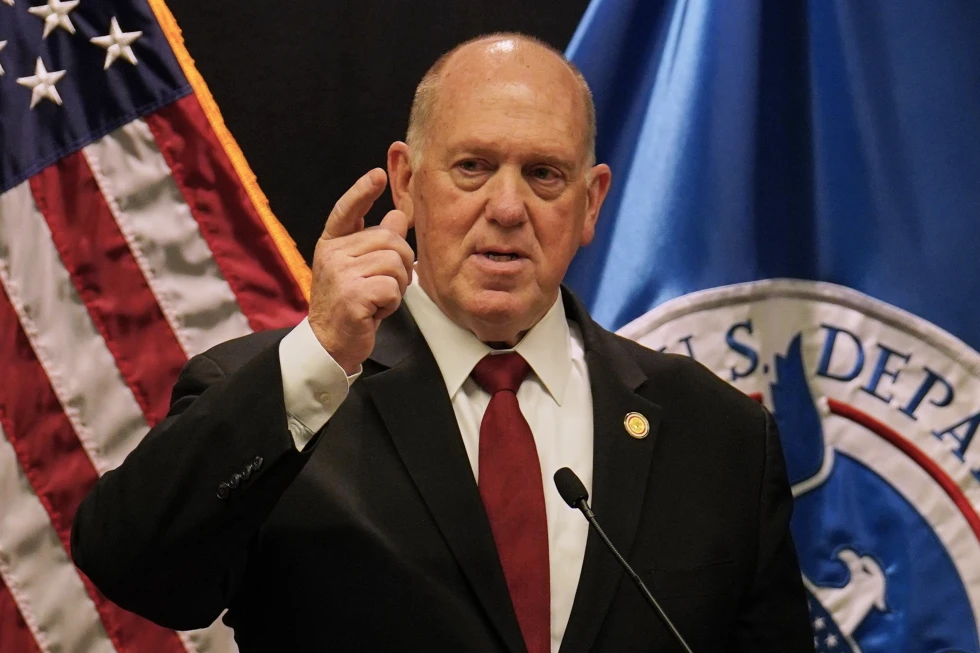

Meanwhile, Prime Minister Takaichi has made reducing Japan's dependence on China in critical sectors like rare minerals and pharmaceuticals a priority. She has also been actively courting Trump, agreeing to raise the defence budget, a contentious move under Japan's pacifist constitution.

She has thanked Trump for his warm words endorsing her, saying she looked forward to visiting the White House this spring and that the potential of our Alliance is LIMITLESS.

Takaichi rejects equidistance between the US and China, seeing the alliance with Washington as central to Japan's security and economic resilience, says Taniguchi.

But Japan cannot afford to choose sides outright.

Prof Kobayashi says that deepening ties with both powers is prudent, particularly as China's property crisis and slowing domestic growth could reshape Beijing's influence in the region.

Takaichi's approach seems to follow the playbook of her mentor, Shinzo Abe: big spending to stimulate growth and low interest rates to support investment.

Abe was dealing with falling prices, a stronger yen, and a far less powerful China.

Takaichi's challenges are graver: Japan is older, its economy is still growing too slowly and the world is in a very different place.