A significant study published in the journal Nature reveals that individuals who get vaccinated for shingles are 20% less likely to develop dementia within seven years compared to unvaccinated individuals, marking an important public health finding. Dr. Paul Harrison, a professor of psychiatry at Oxford, noted that this could be one of the few proactive measures available to mitigate the risk of dementia, as no other effective treatments currently exist. Shingles, caused by the reactivation of the chickenpox virus, can severely impact the nervous system leading to chronic pain and other complications. The study prompts further inquiry into the longevity of the vaccine's protective effects against cognitive decline.

Vaccination Against Shingles Linked to Lower Dementia Risk: Study

Vaccination Against Shingles Linked to Lower Dementia Risk: Study

Recent research highlights the potential of shingles vaccination in reducing dementia risk, emphasizing the broader impacts of viral infections on brain health.

Getting vaccinated against shingles can reduce the risk of developing dementia, a large new study finds. The results provide some of the strongest evidence yet that some viral infections can have effects on brain function years later and that preventing them can help stave off cognitive decline. The study, published on Wednesday in the journal Nature, found that people who received the shingles vaccine were 20 percent less likely to develop dementia in the seven years afterward than those who were not vaccinated.

“If you’re reducing the risk of dementia by 20 percent, that’s quite important in a public health context, given that we don’t really have much else at the moment that slows down the onset of dementia,” said Dr. Paul Harrison, a professor of psychiatry at Oxford. Dr. Harrison was not involved in the new study, but has done other research indicating that shingles vaccines lower dementia risk.

Whether the protection can last beyond seven years can only be determined with further research. But with few currently effective treatments or preventions, Dr. Harrison said, shingles vaccines appear to have “some of the strongest potential protective effects against dementia that we know of that are potentially usable in practice.”

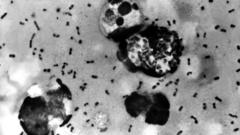

Shingles cases stem from the virus that causes childhood chickenpox, varicella-zoster, which typically remains dormant in nerve cells for decades. As people age and their immune systems weaken, the virus can reactivate and cause shingles, with symptoms like burning, tingling, painful blisters, and numbness. The nerve pain can become chronic and disabling.

“If you’re reducing the risk of dementia by 20 percent, that’s quite important in a public health context, given that we don’t really have much else at the moment that slows down the onset of dementia,” said Dr. Paul Harrison, a professor of psychiatry at Oxford. Dr. Harrison was not involved in the new study, but has done other research indicating that shingles vaccines lower dementia risk.

Whether the protection can last beyond seven years can only be determined with further research. But with few currently effective treatments or preventions, Dr. Harrison said, shingles vaccines appear to have “some of the strongest potential protective effects against dementia that we know of that are potentially usable in practice.”

Shingles cases stem from the virus that causes childhood chickenpox, varicella-zoster, which typically remains dormant in nerve cells for decades. As people age and their immune systems weaken, the virus can reactivate and cause shingles, with symptoms like burning, tingling, painful blisters, and numbness. The nerve pain can become chronic and disabling.