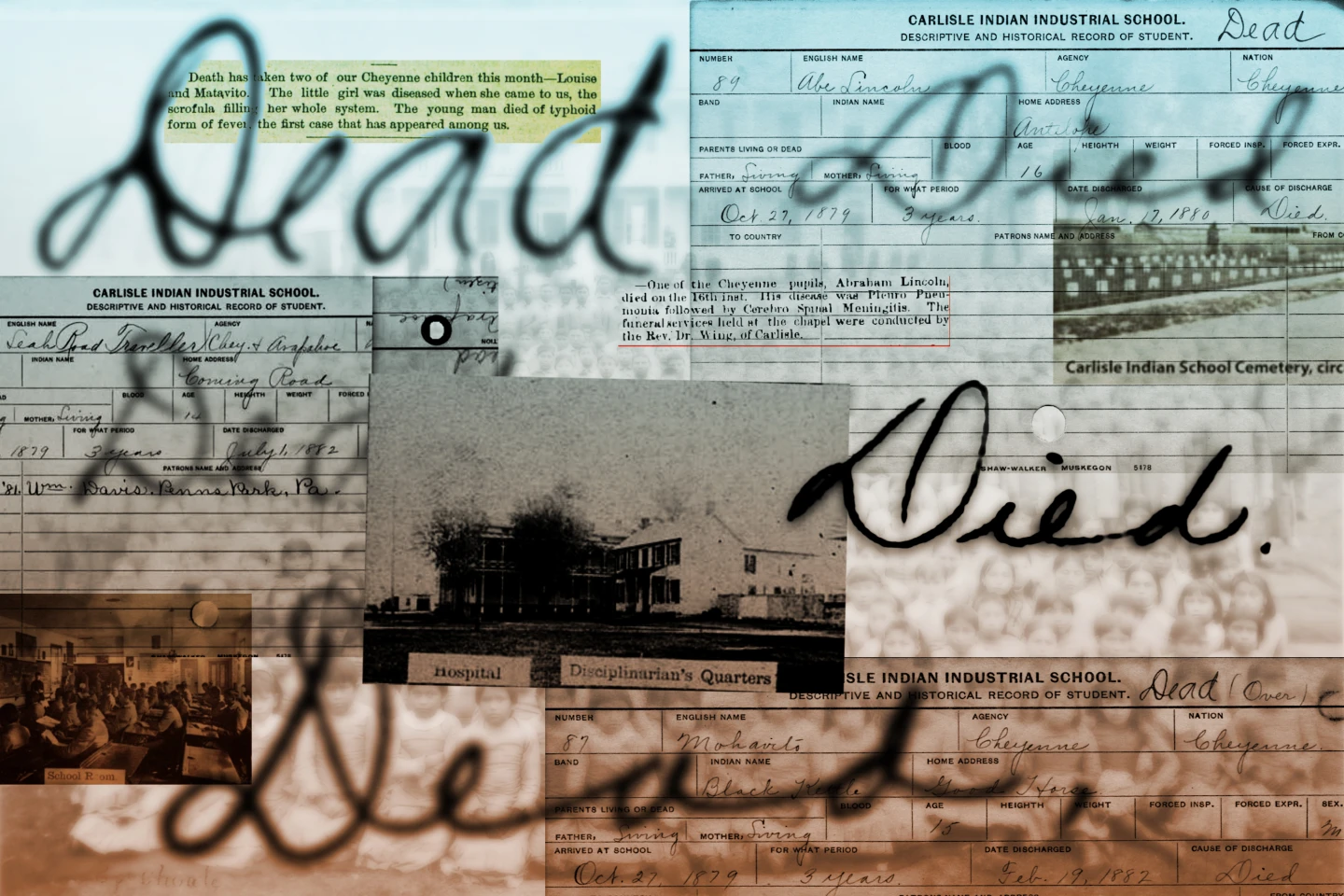

In October 1879, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School opened its doors with a mission that cut to the heart of Native American cultures. It essentially aimed to erase the identities of Native American children like Matavito Horse and Leah Road Traveler, who were among its first students.

Tragically, within a few years, both children died while attending the school. Their remains and those of 15 other Indigenous students were recently exhumed and ceremonially returned to their tribes, part of a long-overdue act of repatriation that reflects the ongoing attempts of these tribes to reclaim their history and honor their lost children.

The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma received 16 children, while one student, Wallace Perryman, was repatriated to the Seminole Nation. Tribal authorities describe the burial ceremonies as vital steps toward healing and justice for families impacted by the historical trauma inflicted during the boarding school era.

The Carlisle Indian School, operational from 1879 to 1918, served more than 7,800 students from various Indigenous backgrounds, many of whom faced harrowing experiences. Reports show at least 973 Native American children died in federally funded schools but some historians believe the numbers to be much higher. Acknowledging this dark history is crucial for the political and social reconciliation of tribal nations with the U.S. government.

As we continue the journey of reclaiming these identities, the legacy of the boarding school era serves as a potent reminder of the resilience among Indigenous communities, reflecting both the challenges faced and the ongoing fight for recognition and repatriation.