For millions across northern India, the November air tastes ashy, the sky looks visibly hazy and merely stepping outside feels like a challenge.

For many, their morning routine starts with checking how bad the air is. But what they see depends entirely on which monitor they use.

Government-backed apps like SAFAR and SAMEER top out at 500 - the upper limit of India's AQI (air quality index) scale, which converts complex data on various pollutants such as PM2.5, PM10, nitrogen dioxide, sulphur dioxide, carbon monoxide and ozone, into a single number.

But private and international trackers such as IQAir and open-source monitoring platform AQI routinely show far higher numbers, often shooting past 600 and even crossing 1,000 on some days.

This contradiction leaves people asking the same question every year: Which numbers should they trust? And why doesn't India officially report air quality beyond 500?

India's official air-quality scale shows readings above 200 pose clear breathing discomfort to most people on prolonged exposure.

Readings above 400 and up to 500 are classified as 'severe' and affect healthy people while also seriously impacting those with existing diseases.

The scale however does not go beyond 500 - a cap set more than a decade ago when the National Air Quality Index was launched.

So why was that threshold introduced?

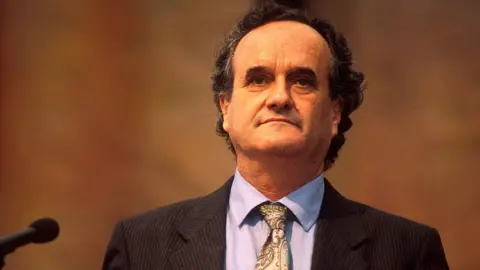

'It was assumed that the health impact would be the same no matter how much higher it goes because we had already hit the worst,' says Gufran Beig, founder director of SAFAR.

He admits that the 500 cap was originally set to avoid creating panic as crossing that mark signalled an alarming situation requiring immediate mitigation.

But this approach effectively flattens the data - anything above 500 is treated the same on official monitors, even if the real concentration is far higher.

'International organisations and portals don't impose such a cap,' says Mr Beig. 'That's why we see numbers going much higher on global platforms.'

Beyond the artificially imposed threshold, there's also a difference in defining hazardous air.

Experts say that globally, there's no universal AQI formula. US, China and the European Union each apply their own pollutant thresholds.

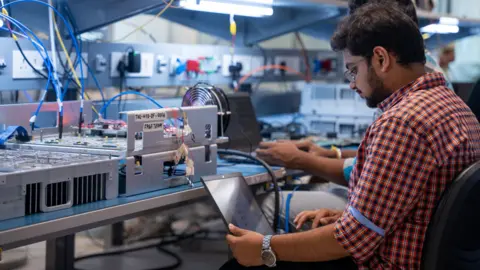

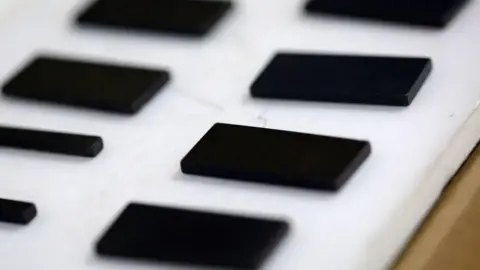

The Indian pollution control board uses Beta Attenuation Monitors (BAMs), which physically measure the mass of particles in the air and are calibrated to strict, standardised metrics for every reading.

In contrast, portals like IQAir rely on sensor-based monitors, which use laser scattering and electrochemical methods to estimate the number of particles suspended in the air. This results in discrepancies in reported pollution levels.

'India's air quality framework hasn't been comprehensively revised since 2009,' says Abhijeet Pathak, a scientist who formerly worked for India's pollution control board. 'National Air Quality index will need to be revised if we want to include the sensor-based data.'

Removing the upper cap is also crucial, says Mr Beig, 'now that most literature available shows health symptoms keep on worsening as the pollution levels increase.'

In the end, India's AQI doesn't stop at 500 because the pollution stops there. It stops at 500 because the system was built with a ceiling.

For many, their morning routine starts with checking how bad the air is. But what they see depends entirely on which monitor they use.

Government-backed apps like SAFAR and SAMEER top out at 500 - the upper limit of India's AQI (air quality index) scale, which converts complex data on various pollutants such as PM2.5, PM10, nitrogen dioxide, sulphur dioxide, carbon monoxide and ozone, into a single number.

But private and international trackers such as IQAir and open-source monitoring platform AQI routinely show far higher numbers, often shooting past 600 and even crossing 1,000 on some days.

This contradiction leaves people asking the same question every year: Which numbers should they trust? And why doesn't India officially report air quality beyond 500?

India's official air-quality scale shows readings above 200 pose clear breathing discomfort to most people on prolonged exposure.

Readings above 400 and up to 500 are classified as 'severe' and affect healthy people while also seriously impacting those with existing diseases.

The scale however does not go beyond 500 - a cap set more than a decade ago when the National Air Quality Index was launched.

So why was that threshold introduced?

'It was assumed that the health impact would be the same no matter how much higher it goes because we had already hit the worst,' says Gufran Beig, founder director of SAFAR.

He admits that the 500 cap was originally set to avoid creating panic as crossing that mark signalled an alarming situation requiring immediate mitigation.

But this approach effectively flattens the data - anything above 500 is treated the same on official monitors, even if the real concentration is far higher.

'International organisations and portals don't impose such a cap,' says Mr Beig. 'That's why we see numbers going much higher on global platforms.'

Beyond the artificially imposed threshold, there's also a difference in defining hazardous air.

Experts say that globally, there's no universal AQI formula. US, China and the European Union each apply their own pollutant thresholds.

The Indian pollution control board uses Beta Attenuation Monitors (BAMs), which physically measure the mass of particles in the air and are calibrated to strict, standardised metrics for every reading.

In contrast, portals like IQAir rely on sensor-based monitors, which use laser scattering and electrochemical methods to estimate the number of particles suspended in the air. This results in discrepancies in reported pollution levels.

'India's air quality framework hasn't been comprehensively revised since 2009,' says Abhijeet Pathak, a scientist who formerly worked for India's pollution control board. 'National Air Quality index will need to be revised if we want to include the sensor-based data.'

Removing the upper cap is also crucial, says Mr Beig, 'now that most literature available shows health symptoms keep on worsening as the pollution levels increase.'

In the end, India's AQI doesn't stop at 500 because the pollution stops there. It stops at 500 because the system was built with a ceiling.