Voters in Switzerland are going to the polls on Sunday to decide on the introduction of electronic identity cards. The plan has already been approved by both houses of parliament, and the Swiss government recommends a yes vote. It is the second nationwide ballot on the issue after voters rejected the idea in 2021 amid concerns over data protection, and unease that the proposed system would be run largely by private companies.

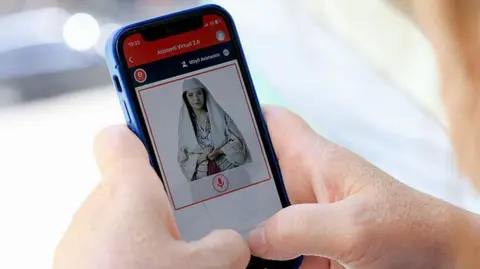

Under the revised proposal, the new system would remain entirely in public hands, the data on the electronic IDs would be stored on users' smartphones rather than centrally, and it would be optional. Citizens can still choose to rely on the national identity card, which has been standard in Switzerland for decades.

To ease privacy concerns, a particular authority seeking information – proof of age or nationality for example – will only be able to check for those specific details. Supporters say the system will make life much easier for everyone, allowing all sorts of bureaucratic procedures - from getting a telephone contract to proving you're old enough to buy a bottle of wine - to happen quickly online.

But Switzerland has a long tradition of protecting its citizens' privacy. The banking secrecy laws, now much diluted, were designed to shield an individual's personal finances from the prying eyes of the state. For years, Google Street View was controversial in Switzerland, and even today, following a ruling by the Swiss Federal Court, images taken close to schools, women's refuges, hospitals or prisons must be automatically blurred before going online. There are also far fewer CCTV cameras in Switzerland than in many of its European neighbours.

Opponents of electronic ID cards, who gathered enough signatures to force another referendum on the issue, argue that this measure too could undermine individual privacy. They also fear that, despite the new restrictions on how data is collected and stored, it could still be used to track people, and for marketing purposes.

Latest opinion polls, however, show voters may this time be ready to give electronic ID a chance. They have already had experience of the government's Covid ID, which was used during the pandemic to show vaccination status and was mandatory to enter restaurants and bars. Initial scepticism turned to satisfaction, when people realised it allowed them, finally, to get out and about again. As for the concerns about marketing of personal data, most Swiss have smartphones and are keen users of social media. The tech giants are already harvesting their likes and dislikes, many voters realise, so believe that allowing the Swiss authorities to check on a few details from time to time can't really make a big difference.

Under the revised proposal, the new system would remain entirely in public hands, the data on the electronic IDs would be stored on users' smartphones rather than centrally, and it would be optional. Citizens can still choose to rely on the national identity card, which has been standard in Switzerland for decades.

To ease privacy concerns, a particular authority seeking information – proof of age or nationality for example – will only be able to check for those specific details. Supporters say the system will make life much easier for everyone, allowing all sorts of bureaucratic procedures - from getting a telephone contract to proving you're old enough to buy a bottle of wine - to happen quickly online.

But Switzerland has a long tradition of protecting its citizens' privacy. The banking secrecy laws, now much diluted, were designed to shield an individual's personal finances from the prying eyes of the state. For years, Google Street View was controversial in Switzerland, and even today, following a ruling by the Swiss Federal Court, images taken close to schools, women's refuges, hospitals or prisons must be automatically blurred before going online. There are also far fewer CCTV cameras in Switzerland than in many of its European neighbours.

Opponents of electronic ID cards, who gathered enough signatures to force another referendum on the issue, argue that this measure too could undermine individual privacy. They also fear that, despite the new restrictions on how data is collected and stored, it could still be used to track people, and for marketing purposes.

Latest opinion polls, however, show voters may this time be ready to give electronic ID a chance. They have already had experience of the government's Covid ID, which was used during the pandemic to show vaccination status and was mandatory to enter restaurants and bars. Initial scepticism turned to satisfaction, when people realised it allowed them, finally, to get out and about again. As for the concerns about marketing of personal data, most Swiss have smartphones and are keen users of social media. The tech giants are already harvesting their likes and dislikes, many voters realise, so believe that allowing the Swiss authorities to check on a few details from time to time can't really make a big difference.