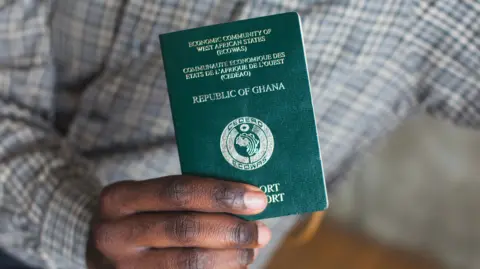

Ghana's cashew industry is at a crossroads, facing mounting challenges as farmers and entrepreneurs strive to increase local processing and profitability. On the streets of Accra, the stark contrast in pricing is evident, as a small bag of roasted cashews sells for a staggering markup compared to the raw product sourced directly from local farmers.

Ghana stands as the world's third-largest exporter of unprocessed cashew nuts, trailing behind Ivory Coast and Cambodia. Approximately 300,000 Ghanaians rely on cashew farming for their livelihood, yet they face an uphill battle. Nashiru Seydou, a farmer from the northeast region, highlights the obstacles posed by unstable supply chains and unpredictable prices. "We are struggling. We can use the sunlight, the fertile land, to create more jobs," he states. Currently, Seydou receives only around $50 for a 100kg sack of unshelled cashews, a stark contrast to the profits made down the line.

Bright Simons, an economic expert, reveals the disparity between what farmers earn and what retailers profit: while farmers sell their nuts for about $500 a ton, roasters can sell them for $20,000 to $40,000 per ton. Ghana produces about 180,000 tons of cashews each year, with over 80% destined for export as raw nuts, generating around $300 million in revenue. However, the country misses out on the larger profits available from processed and roasted cashews.

Mildred Akotia, CEO of Akwaaba Fine Foods, is making headway in local processing but faces significant challenges. With her company processing only 25 tons annually, she insists that high-interest loans from local banks, sometimes approaching 30%, hinder growth. "As a manufacturer, you tell me how large your margins are that you can afford that kind of interest?" she questions. This financial barrier results in less than 20% of Ghana's cashews being processed locally, with the majority sent abroad for further processing.

The narrative isn't unique to cashews; similar inefficiencies exist in other agricultural products, such as rice. In a puzzling trade twist, some processed cashews leave Ghana only to return packaged—at similar prices—despite significant transportation costs.

A governmental effort in 2016 to ban the export of raw cashews to bolster domestic processing was swiftly abandoned following backlash from farmers and traders. Current discussions include potential tariffs on raw exports and restrictions on purchasing techniques, but analysts like Simons argue that the focus should also be on improving local business practices to create efficient, scalable operations.

Moreover, notable economists like Prof. Daron Acemoglu stress the importance of enhancing market access for processed goods and addressing infrastructural challenges within Ghana. Efforts to connect local businesses to global markets are critical for unlocking the industry's potential.

Akotia remains optimistic; she hopes to develop her logistics operation to streamline processing and better meet demand. "There's a ready market both locally and internationally. My dream is to give a facelift to Ghanaian processed foods," she asserts. As Ghana's cashew industry navigates these complexities, the path forward will require innovative solutions and commitment to local empowerment and market growth.

Ghana stands as the world's third-largest exporter of unprocessed cashew nuts, trailing behind Ivory Coast and Cambodia. Approximately 300,000 Ghanaians rely on cashew farming for their livelihood, yet they face an uphill battle. Nashiru Seydou, a farmer from the northeast region, highlights the obstacles posed by unstable supply chains and unpredictable prices. "We are struggling. We can use the sunlight, the fertile land, to create more jobs," he states. Currently, Seydou receives only around $50 for a 100kg sack of unshelled cashews, a stark contrast to the profits made down the line.

Bright Simons, an economic expert, reveals the disparity between what farmers earn and what retailers profit: while farmers sell their nuts for about $500 a ton, roasters can sell them for $20,000 to $40,000 per ton. Ghana produces about 180,000 tons of cashews each year, with over 80% destined for export as raw nuts, generating around $300 million in revenue. However, the country misses out on the larger profits available from processed and roasted cashews.

Mildred Akotia, CEO of Akwaaba Fine Foods, is making headway in local processing but faces significant challenges. With her company processing only 25 tons annually, she insists that high-interest loans from local banks, sometimes approaching 30%, hinder growth. "As a manufacturer, you tell me how large your margins are that you can afford that kind of interest?" she questions. This financial barrier results in less than 20% of Ghana's cashews being processed locally, with the majority sent abroad for further processing.

The narrative isn't unique to cashews; similar inefficiencies exist in other agricultural products, such as rice. In a puzzling trade twist, some processed cashews leave Ghana only to return packaged—at similar prices—despite significant transportation costs.

A governmental effort in 2016 to ban the export of raw cashews to bolster domestic processing was swiftly abandoned following backlash from farmers and traders. Current discussions include potential tariffs on raw exports and restrictions on purchasing techniques, but analysts like Simons argue that the focus should also be on improving local business practices to create efficient, scalable operations.

Moreover, notable economists like Prof. Daron Acemoglu stress the importance of enhancing market access for processed goods and addressing infrastructural challenges within Ghana. Efforts to connect local businesses to global markets are critical for unlocking the industry's potential.

Akotia remains optimistic; she hopes to develop her logistics operation to streamline processing and better meet demand. "There's a ready market both locally and internationally. My dream is to give a facelift to Ghanaian processed foods," she asserts. As Ghana's cashew industry navigates these complexities, the path forward will require innovative solutions and commitment to local empowerment and market growth.