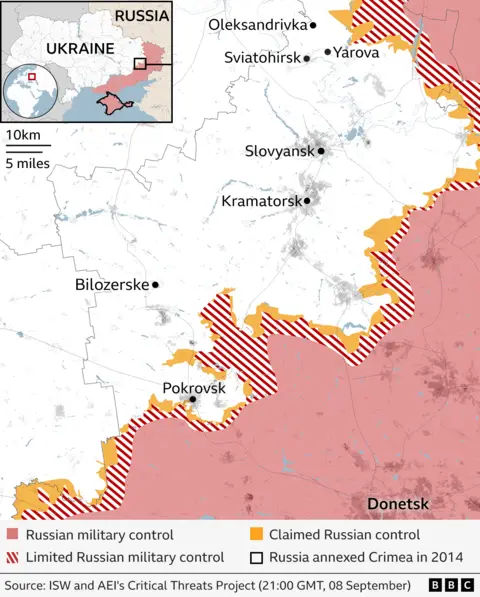

The Donetsk region of eastern Ukraine has long been in Moscow's sights. Vladimir Putin reportedly says he'll freeze the war in return for full control of it. Russia already controls 70% of Donetsk and nearly all of neighbouring Luhansk - and is making slow but steady advances.

I'm heading to the front-line Donetsk town of Dobropillia with two humanitarian volunteers, just 8km (five miles) from Russia's positions. They're on a mission to bring the sick, elderly, and children to safer ground.

At first, it goes like clockwork. We speed into the town in an armoured car, equipped with rooftop drone-jamming equipment, hitting 130km/h (80mph). The road is covered in tall green netting which obscures visibility from above - protecting it from Russian drones.

This is their second trip of the morning, and the streets are mostly empty. The few remaining residents only leave their homes to quickly collect supplies. Russian attacks come daily.

The town already looks abandoned and has been without water for a week. Every building we pass has been damaged, with some reduced to ruins.

In the previous five days, Laarz, a 31-year-old German, and Varia, a 19-year-old Ukrainian, who work for the charity Universal Aid Ukraine, have made dozens of trips to evacuate people.

A week earlier, small groups of Russian troops breached the defences around the town, sparking fears that the front line of Ukraine's so-called 'fortress belt' - some of the most heavily defended parts of the Ukrainian front - could collapse.

Extra troops were rushed to the area and Ukrainian authorities say the situation has been stabilised. But most of Dobropillia's residents feel it's time to go.

As the evacuation team arrives, Vitalii Kalinichenko, 56, is waiting on the doorstep of his apartment block, with a plastic bag full of belongings in hand. 'My windows were all smashed, look, they all flew out on the second floor. I'm the only one left,' he says.

He's wearing a grey t-shirt and black shorts, and his right leg is bandaged. Mr Kalinichenko points to a crater beyond some rose bushes where a Shahed drone crashed a couple of nights earlier, shattering his windows and cutting his leg.

As we are about to leave, Laarz spots a drone overhead and we take cover again under trees. His handheld drone detector shows multiple Russian drones in the area.

An older woman in a summer dress and straw hat is walking by with a shopping trolley. He warns her about the drone, and she quickens her pace. An explosion hits nearby, its sound echoing off the nearby apartment blocks.

But before we can attempt to leave, there is still another family to be rescued, just around the corner. Laarz goes on foot to find them, switching off the idling vehicle's drone-jamming equipment to save battery power. 'If you hear a drone, it's the two switches in the middle console, turn it on,' he says as he disappears around the corner. The jammer is only effective against some Russian drones.

Laarz returns with more evacuees, and with drones still in the air above, drives out of town even faster than he arrived. Inside the evacuation convoy, I sit beside Anton, 31. His mother stayed behind. She cried as he departed, and he hopes she will leave too soon.

In war, front lines shift, towns are lost and won and lost again. Anton urges for negotiations, indicating the necessity for a peaceful resolution without bloodshed. However, Varia expresses skepticism about trusting Putin, highlighting enduring conflicts and strong desires for peace among the Ukrainian populace. As the evacuation team continues its work in such dangerous surroundings, the grim reality of the situation remains ever-present, and the future stability of Donetsk hangs precariously in the balance.

I'm heading to the front-line Donetsk town of Dobropillia with two humanitarian volunteers, just 8km (five miles) from Russia's positions. They're on a mission to bring the sick, elderly, and children to safer ground.

At first, it goes like clockwork. We speed into the town in an armoured car, equipped with rooftop drone-jamming equipment, hitting 130km/h (80mph). The road is covered in tall green netting which obscures visibility from above - protecting it from Russian drones.

This is their second trip of the morning, and the streets are mostly empty. The few remaining residents only leave their homes to quickly collect supplies. Russian attacks come daily.

The town already looks abandoned and has been without water for a week. Every building we pass has been damaged, with some reduced to ruins.

In the previous five days, Laarz, a 31-year-old German, and Varia, a 19-year-old Ukrainian, who work for the charity Universal Aid Ukraine, have made dozens of trips to evacuate people.

A week earlier, small groups of Russian troops breached the defences around the town, sparking fears that the front line of Ukraine's so-called 'fortress belt' - some of the most heavily defended parts of the Ukrainian front - could collapse.

Extra troops were rushed to the area and Ukrainian authorities say the situation has been stabilised. But most of Dobropillia's residents feel it's time to go.

As the evacuation team arrives, Vitalii Kalinichenko, 56, is waiting on the doorstep of his apartment block, with a plastic bag full of belongings in hand. 'My windows were all smashed, look, they all flew out on the second floor. I'm the only one left,' he says.

He's wearing a grey t-shirt and black shorts, and his right leg is bandaged. Mr Kalinichenko points to a crater beyond some rose bushes where a Shahed drone crashed a couple of nights earlier, shattering his windows and cutting his leg.

As we are about to leave, Laarz spots a drone overhead and we take cover again under trees. His handheld drone detector shows multiple Russian drones in the area.

An older woman in a summer dress and straw hat is walking by with a shopping trolley. He warns her about the drone, and she quickens her pace. An explosion hits nearby, its sound echoing off the nearby apartment blocks.

But before we can attempt to leave, there is still another family to be rescued, just around the corner. Laarz goes on foot to find them, switching off the idling vehicle's drone-jamming equipment to save battery power. 'If you hear a drone, it's the two switches in the middle console, turn it on,' he says as he disappears around the corner. The jammer is only effective against some Russian drones.

Laarz returns with more evacuees, and with drones still in the air above, drives out of town even faster than he arrived. Inside the evacuation convoy, I sit beside Anton, 31. His mother stayed behind. She cried as he departed, and he hopes she will leave too soon.

In war, front lines shift, towns are lost and won and lost again. Anton urges for negotiations, indicating the necessity for a peaceful resolution without bloodshed. However, Varia expresses skepticism about trusting Putin, highlighting enduring conflicts and strong desires for peace among the Ukrainian populace. As the evacuation team continues its work in such dangerous surroundings, the grim reality of the situation remains ever-present, and the future stability of Donetsk hangs precariously in the balance.