The first day Gisèle Pelicot walked up the steps of the courthouse in Avignon in September 2024, she was an anonymous retired grandmother.

Within weeks, this diminutive 72-year-old - the victim at the centre of the largest rape trial in French history, involving 51 men including her husband - had become a feminist icon.

She was last seen in public when the verdicts - all guilty - were handed down in December. By then, crowds of supporters were chanting her name.

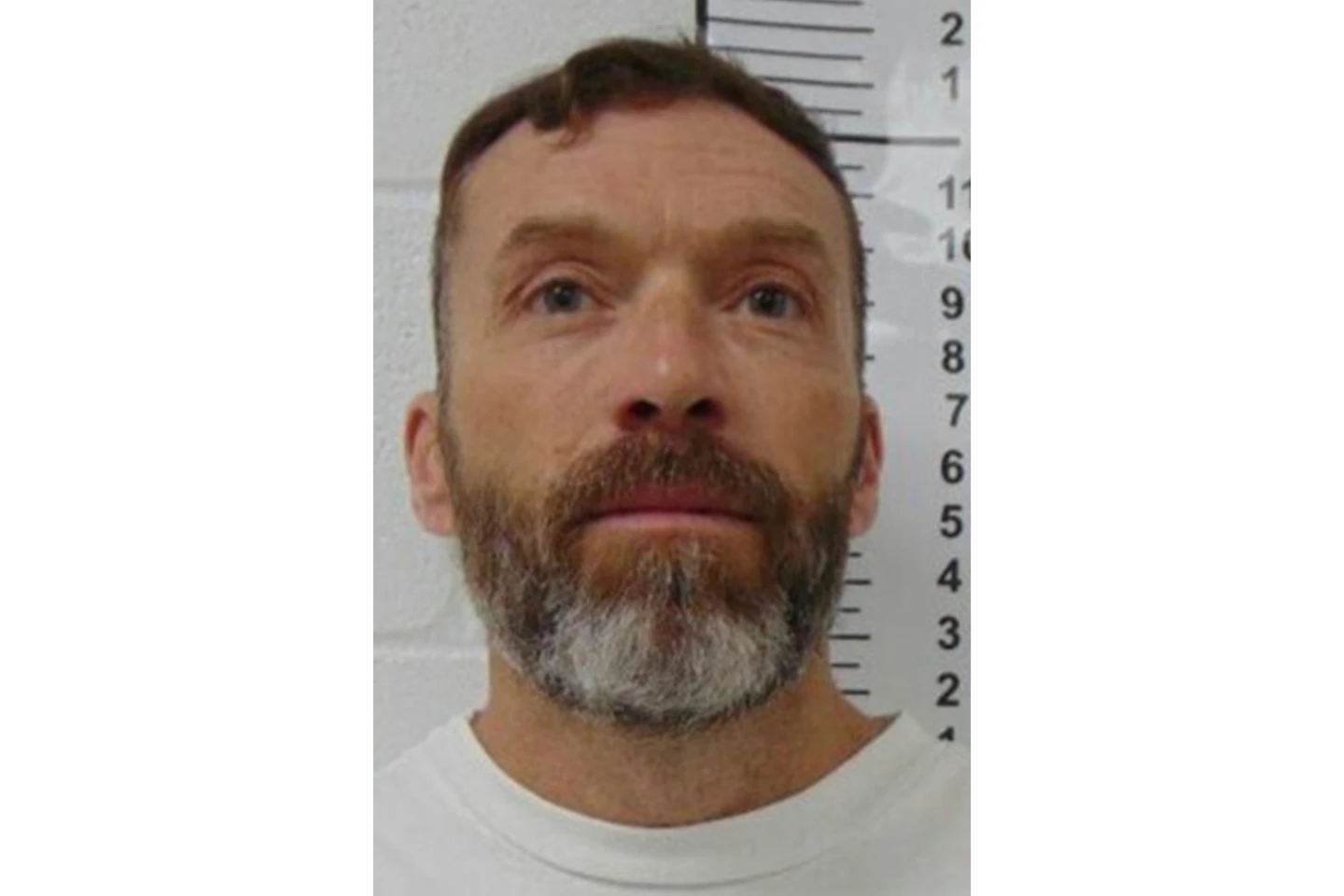

On Monday Gisèle Pelicot returns to court, this time in Nîmes, for the appeal of the only one of the 51 defendants to challenge his sentence: Husamettin Dogan, 44, a married father of one.

Between September and December last year, Gisèle's bleak story travelled the world. For over a decade, she had been drugged unconscious by her husband Dominique and raped by dozens of men he had recruited on internet chat rooms.

Dominique Pelicot filmed the assaults and neatly catalogued them on a hard disk, which allowed investigators to track down the majority of the individuals involved. Around 20 could not be identified and remain at large.

After a trial lasting 16 weeks, 46 men were found guilty of rape, two of attempted rape and two of sexual assault. Dominique Pelicot was handed the maximum jail sentence of 20 years.

Husamettin Dogan's appeal next week will, in effect, be a retrial. The videos of Gisèle's rape will be shown in court again, and Pelicot will be present – this time, though, only as a witness.

While she is not obliged to, Gisèle too will attend the proceedings.

Everyone would have understood if she hadn't come because, well, she is trying to resume a normal life, one of her lawyers, Stéphane Babonneau, told the BBC. But she feels she needs to be there and has a responsibility to be there until the end of the proceedings.

In December, Dogan was found guilty of aggravated rape and sentenced to nine years in prison. Due to health reasons he was handed a deferred custody warrant and is not currently in jail. He is reportedly appealing both the guilty verdict and the length of his sentence.

As was the case for many of the other 51 men, Dogan's defence hinged on the argument he could not be guilty of raping Gisèle because he had not realised she would be unconscious. Pelicot rejected this argument, saying he had made it abundantly clear to the men he recruited online that his wife would be drugged.

In his statement to the court last year Dogan did admit telling Pelicot that his wife looked dead. Still, he vehemently pushed back against the accusations levelled at him. I don't accept being labelled a rapist, he protested. It's too heavy a burden for me to carry.

Although 16 other defendants also initially lodged appeals, Dogan was the only one who has pushed ahead with it.

Unlike the first trial, Dogan's appeal will be judged by a jury made up of nine members of the public who will decide on both his conviction and the length of his jail term.

If he loses his appeal, the trial's huge resonance and media coverage may mean the jury ends up being less lenient than the judges were last December.

It's a real risk and I think that's why so many men withdrew their appeals, French magistrate Magali Lafourcade told the BBC.

She believes the Pelicot case has had a significant effect on French society and that jurors are bound to have a new understanding of societal issues around rape and consent.

Although last year she only addressed the court on a handful of occasions, whenever she did so Gisèle said she was speaking out to help other victims of rape: I want them to say: if Madame Pelicot did it, I can too.

Shame must change sides from the victim to the perpetrator, she insisted. This reasoning was at the heart of her decision to waive her anonymity, open the trial to the media and the public, and push for the videos of her rapes to be shown in court.

It was a momentous decision, and the reason the trial garnered worldwide resonance. Since the verdicts were handed down, Gisèle Pelicot has been named one of Time's 100 most influential people. She was also awarded numerous prizes including the French Legion d'Honneur and has been sent a personal letter by Queen Camilla.

But by and large, after those months in the public eye, Gisèle was able to regain the privacy she had been denied for so long. Soon after the end of the trial she retreated to Île de Ré, a small island off France's Atlantic coast.

For a time, the only images of her to emerge were occasional selfies posted by her son Florian on social media, showing her sitting by the sea, beaming at the camera.

That privacy did not last. Last spring, glossy magazine Paris Match published paparazzi pictures of her and her new partner strolling on Île de Ré.

Many noted it was yet another instance of personal images being taken and shared without her consent. Her legal team took the publication to court, arguing that Gisèle's decision to waive her anonymity for the duration of the trial did not mean giving up her right to a private life.

At the heart of the family split is a moment that shook the court last November, when Gisèle was asked about photos found on Pelicot's computer showing their semi-naked daughter Caroline, apparently asleep and wearing unfamiliar underwear.

Caroline Darian has always insisted the photos prove her father drugged and assaulted her too – and in March pressed charges against him. He has always denied sexually assaulting his daughter.

Caroline recalled how, up on the stand, Gisèle refused to address the accusations of incest against her husband. And it's as if the ground opened up underneath my feet. Her silence spoke volumes. It marked a point of no-return.

I was her only daughter, she should not have let go of my hand, especially not then, Ms Darian wrote. Devastated by what she saw as her mother's rejection, she left the courtroom.

Ms Darian – who has since thrown herself into a battle against chemical submission (drug-facilitated sexual assault) – has said she and Gisèle no longer speak, and she is not expected to attend next week's trial.

Her older brother David, who has been vocal in his support for her, will also stay away.

His son Nathan, now 19, pressed charges against Dominique Pelicot after the trial reportedly triggered childhood memories of sexual abuse. When the charges were dismissed earlier this year for lack of evidence, Caroline said she was indignant and disgusted.

In the same way last year's trial reverberated far beyond the courtroom in Avignon, sparking urgent conversations nationwide over rape, consent and gender violence, Dominique Pelicot's crimes rippled through the family, tearing it apart.