The Heartbreaking Fight of Greenlandic Mothers for Their Children

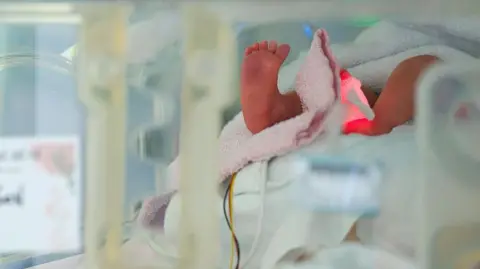

When Keira's daughter was born last November, she was given two hours with her before the baby was taken into care.

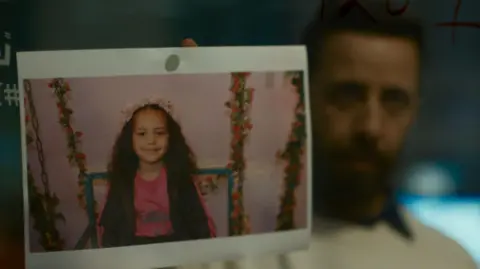

Right when she came out, I started counting the minutes, Keira, 39, recalls. I kept looking at the clock to see how long we had. When the moment came for Zammi to be taken from her arms, Keira says she sobbed uncontrollably, whispering sorry to her baby. It felt like a part of my soul died.

Keira is one of many Greenlandic families living on the Danish mainland who are fighting to get their children returned to them after they were removed by social services. In such cases, babies and children were taken away after parental competency tests—known in Denmark as FKUs—were used to assess whether they were fit to be parents.

In May this year, the Danish government banned the use of these tests on Greenlandic families after decades of criticism, although they continue to be used on other families in Denmark. The assessments, which usually take months, are often seen as biased against Greenlandic culture since they are based on Danish norms and administered in Danish.

Greenlandic parents are 5.6 times more likely to have their children taken into care compared to Danish parents, revealing systemic inequalities that affect many families like Keira and her children.

Keira's struggles are echoed in the story of Johanne and Ulrik, who also faced the loss of their son shortly after his birth due to similar assessments. The couple recount the heartbreak and the difficult, often dehumanizing process of having their child taken away, highlighting the flaws in the testing methods and the cultural misalignments involved.

Despite the recent changes, government reviews have only resulted in minimal action, with very few cases being re-evaluated, leaving many families like Keira's in a painful limbo. she continues to fight for her daughter Zammi's return, refusing to lose hope despite the odds stacked against her.

Keira and other mothers are determined to share their stories, advocating for a reevaluation of the criteria used to assess parental fitness and demanding cultural sensitivity in these assessments to prevent future heartbreak.