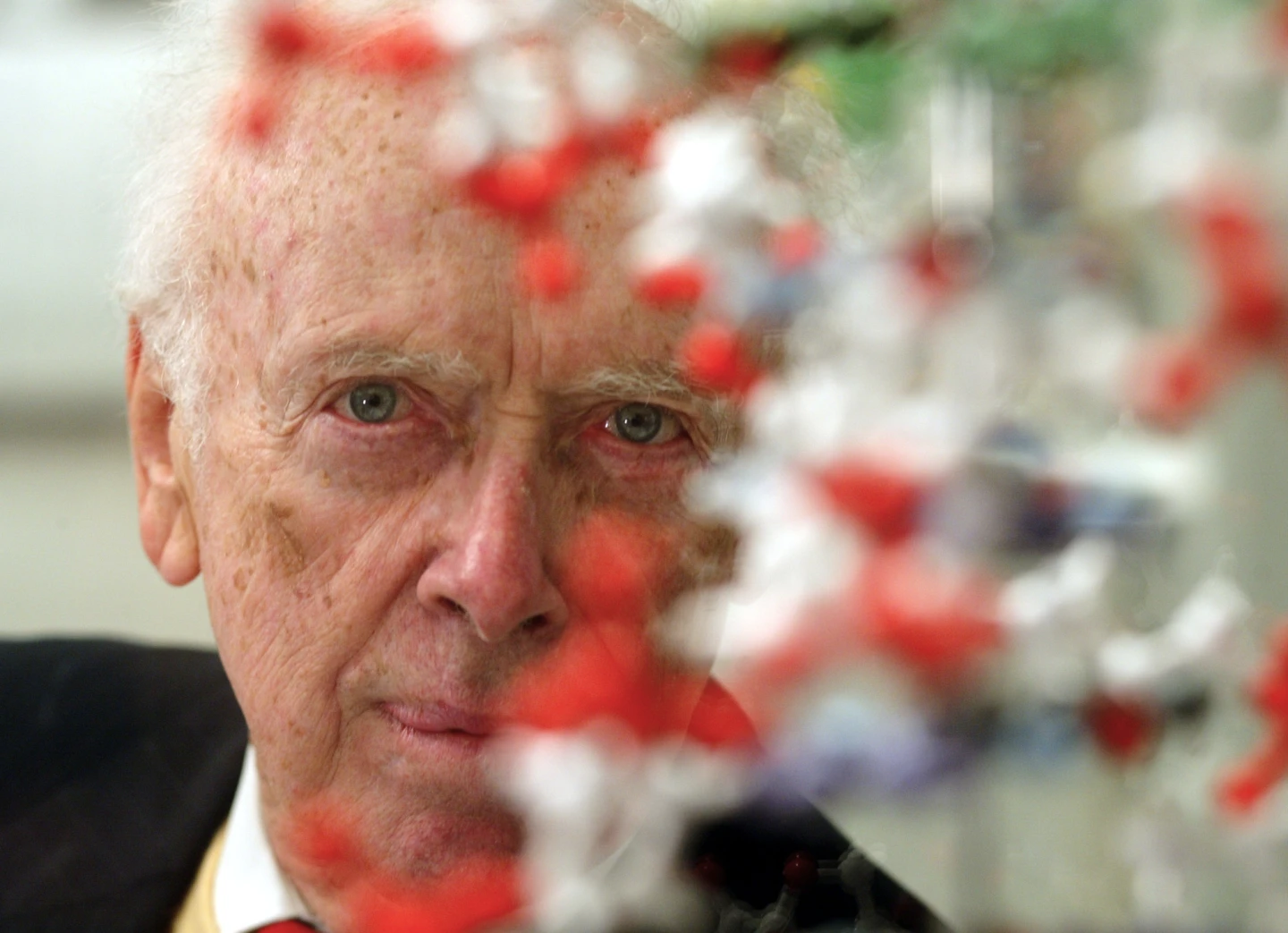

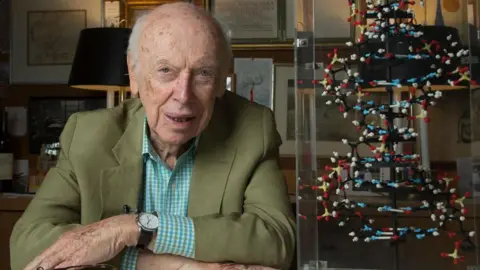

James D. Watson, whose co-discovery of the twisted-ladder structure of DNA in 1953 helped light the long fuse on a revolution in medicine, crime fighting, genealogy, and ethics, has died. He was 97.

The breakthrough — made when the brash, Chicago-born Watson was just 24 — turned him into a hallowed figure in the world of science for decades. However, near the end of his life, he faced condemnation and professional censure for offensive remarks, including saying Black people are less intelligent than white people.

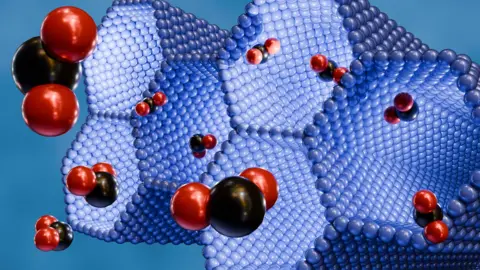

Watson shared a 1962 Nobel Prize with Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins for discovering that deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA, is a double helix, consisting of two strands that coil around each other to create what resembles a long, gently twisting ladder. This realization was pivotal, as it instantly suggested how hereditary information is stored and how cells duplicate their DNA when they divide.

Even among non-scientists, the double helix became a universally recognized symbol of science, appearing in various creative works, including those of Salvador Dali and on a British postage stamp.

Watson's discovery opened the door to modern advancements such as modifying the genetic makeup of living organisms, treating diseases by gene insertion, and using DNA samples to identify human remains and criminal suspects. Still, this genetic advancement also raised a host of ethical questions regarding the potential consequences of genetic alterations.

“Francis Crick and I made the discovery of the century, that was pretty clear,” Watson once said. He later reflected on the unforeseen impact of the double helix on both science and society. Despite never replicating such a groundbreaking finding, Watson contributed significantly to science by authoring influential textbooks, guiding genomic mapping projects, and mentoring promising scientists.

Watson passed away in hospice care after a brief illness, his son reported. His enduring legacy will always be intertwined with both his monumental scientific achievements and the controversial comments that increasingly overshadowed his contributions to genetics. As noted by Dr. Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health, Watson's later remarks, particularly on race, were profoundly misguided and hurtful, illustrating a complex legacy of brilliance shadowed by troubling views.

The breakthrough — made when the brash, Chicago-born Watson was just 24 — turned him into a hallowed figure in the world of science for decades. However, near the end of his life, he faced condemnation and professional censure for offensive remarks, including saying Black people are less intelligent than white people.

Watson shared a 1962 Nobel Prize with Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins for discovering that deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA, is a double helix, consisting of two strands that coil around each other to create what resembles a long, gently twisting ladder. This realization was pivotal, as it instantly suggested how hereditary information is stored and how cells duplicate their DNA when they divide.

Even among non-scientists, the double helix became a universally recognized symbol of science, appearing in various creative works, including those of Salvador Dali and on a British postage stamp.

Watson's discovery opened the door to modern advancements such as modifying the genetic makeup of living organisms, treating diseases by gene insertion, and using DNA samples to identify human remains and criminal suspects. Still, this genetic advancement also raised a host of ethical questions regarding the potential consequences of genetic alterations.

“Francis Crick and I made the discovery of the century, that was pretty clear,” Watson once said. He later reflected on the unforeseen impact of the double helix on both science and society. Despite never replicating such a groundbreaking finding, Watson contributed significantly to science by authoring influential textbooks, guiding genomic mapping projects, and mentoring promising scientists.

Watson passed away in hospice care after a brief illness, his son reported. His enduring legacy will always be intertwined with both his monumental scientific achievements and the controversial comments that increasingly overshadowed his contributions to genetics. As noted by Dr. Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health, Watson's later remarks, particularly on race, were profoundly misguided and hurtful, illustrating a complex legacy of brilliance shadowed by troubling views.