PHILADELPHIA (AP) — Archaeologists studying ancient civilizations in northern Iraq during the 1930s also befriended the nearby Yazidi community, documenting their daily lives in photographs that were rediscovered after the Islamic State militant group devastated the tiny religious minority.

The black-and-white images ended up scattered among the 2,000 or so photographs from the excavation kept at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, which led the ambitious dig.

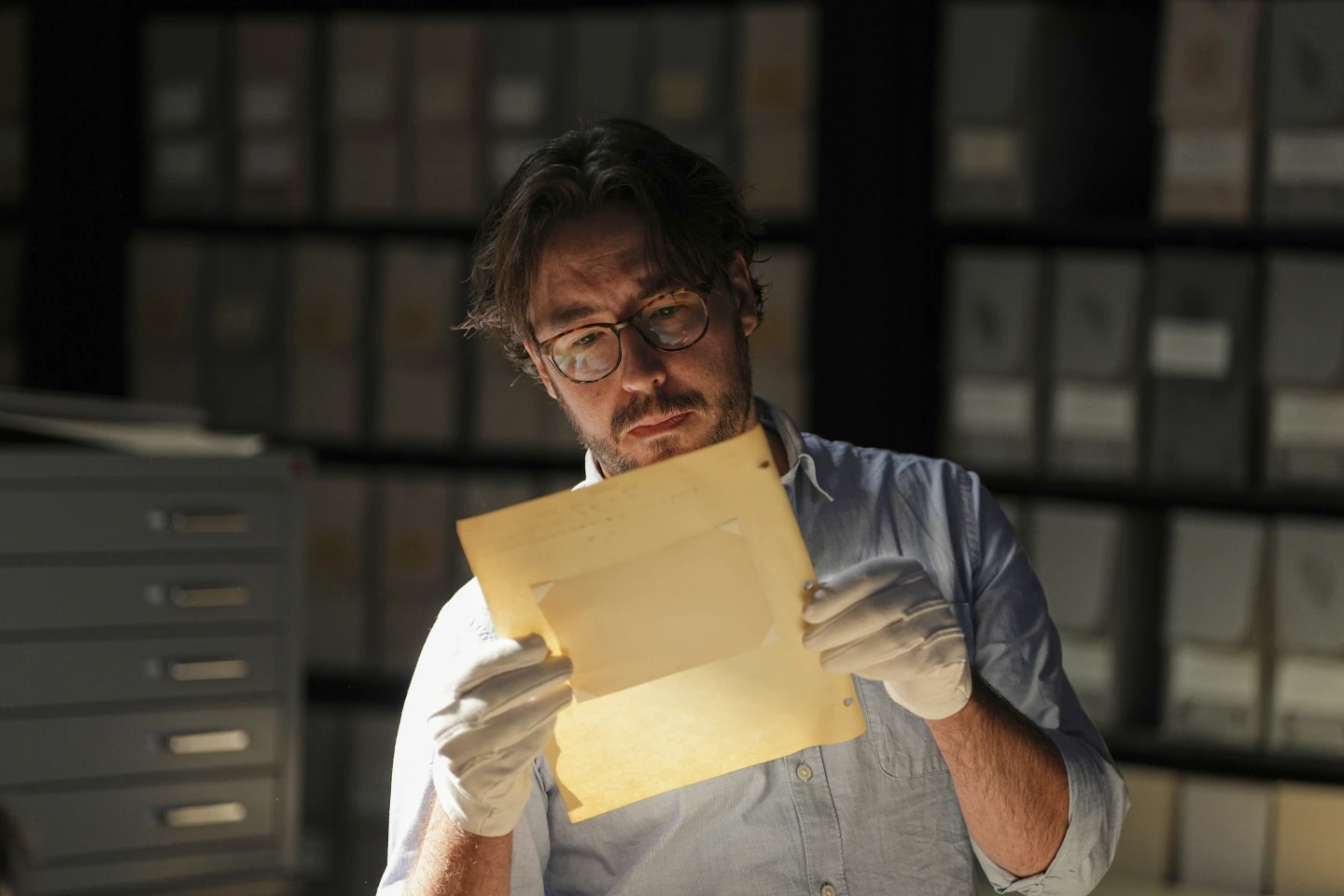

One photo — a Yazidi shrine — caught the eye of Penn doctoral student Marc Marin Webb in 2022, nearly a decade after it was destroyed by IS extremists plundering the region. Webb and others began scouring museum files and gathered almost 300 photos to create a visual archive of the Yazidi people, one of Iraq’s oldest religious minorities.

The systematic attacks, which the United Nations called a genocide, killed thousands of Yazidis and sent thousands more into exile or sexual slavery. It also destroyed much of their built heritage and cultural history, and the small community has since become splintered around the world.

Ansam Basher, now a teacher in England, was overwhelmed with emotion when she saw the photos, particularly a batch from her grandparents’ wedding day in the early 1930s. “No one would imagine that a person my age would lose their history because of the ISIS attack,” said Basher. “My albums, my childhood photos... disappeared. And now to see that my grandfather and great-grandfather’s photo all of a sudden just come to life again, this is something I’m really happy about.”

The archive documents Yazidi people, places, and traditions that IS sought to erase. Marin Webb is working with Nathaniel Brunt, a Toronto documentarian, to share it with the community through exhibits in the region and in digital form with the Yazidi diaspora.

The first exhibits took place in the region in April, when Yazidis gather to celebrate the New Year. Some exhibited outdoors in areas the photos documented nearly a century earlier. “It was perceived as a beautiful way to bring memory back, a memory that was directly threatened through the ethnic cleansing campaign,” Marin Webb said.

Basher’s brother recognized their grandparents in the exhibit, which helped the researchers fill in some blanks. Photos revealed the elaborate traditions of a Yazidi wedding, drawn from a long-lost past.

Her grandfather was a key figure in the community, hosting archaeological crews at his café. With this rediscovery, the images serve as a potent resistance against the destruction of Yazidi heritage and culture, emphasizing their humanity beyond the violence that has long overshadowed their story. As Basher notes, displaying these photographs fosters understanding and respect for a community that has been deeply misunderstood and marginalized.

The black-and-white images ended up scattered among the 2,000 or so photographs from the excavation kept at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, which led the ambitious dig.

One photo — a Yazidi shrine — caught the eye of Penn doctoral student Marc Marin Webb in 2022, nearly a decade after it was destroyed by IS extremists plundering the region. Webb and others began scouring museum files and gathered almost 300 photos to create a visual archive of the Yazidi people, one of Iraq’s oldest religious minorities.

The systematic attacks, which the United Nations called a genocide, killed thousands of Yazidis and sent thousands more into exile or sexual slavery. It also destroyed much of their built heritage and cultural history, and the small community has since become splintered around the world.

Ansam Basher, now a teacher in England, was overwhelmed with emotion when she saw the photos, particularly a batch from her grandparents’ wedding day in the early 1930s. “No one would imagine that a person my age would lose their history because of the ISIS attack,” said Basher. “My albums, my childhood photos... disappeared. And now to see that my grandfather and great-grandfather’s photo all of a sudden just come to life again, this is something I’m really happy about.”

The archive documents Yazidi people, places, and traditions that IS sought to erase. Marin Webb is working with Nathaniel Brunt, a Toronto documentarian, to share it with the community through exhibits in the region and in digital form with the Yazidi diaspora.

The first exhibits took place in the region in April, when Yazidis gather to celebrate the New Year. Some exhibited outdoors in areas the photos documented nearly a century earlier. “It was perceived as a beautiful way to bring memory back, a memory that was directly threatened through the ethnic cleansing campaign,” Marin Webb said.

Basher’s brother recognized their grandparents in the exhibit, which helped the researchers fill in some blanks. Photos revealed the elaborate traditions of a Yazidi wedding, drawn from a long-lost past.

Her grandfather was a key figure in the community, hosting archaeological crews at his café. With this rediscovery, the images serve as a potent resistance against the destruction of Yazidi heritage and culture, emphasizing their humanity beyond the violence that has long overshadowed their story. As Basher notes, displaying these photographs fosters understanding and respect for a community that has been deeply misunderstood and marginalized.