The upcoming referendum in Italy seeks to halve the wait time for citizenship applications but faces strong opposition.

Citizenship and Identity: Italy's Polarising Referendum Sparks Debate

Citizenship and Identity: Italy's Polarising Referendum Sparks Debate

As Italians prepare to vote on a landmark citizenship measure, discussions around identity and belonging take center stage.

Sonny Olumati, a 39-year-old dancer and activist born in Rome, encapsulates the struggles of many in Italy as he illustrates the challenges of living in a country that doesn’t recognize him as a citizen. Despite being raised in Italy and loving the country he calls home, he lives under the shadow of his Nigerian passport. “Not having citizenship is like… being rejected from your country,” he says, highlighting a deep-rooted sense of alienation.

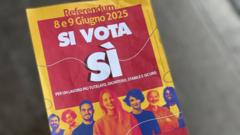

On Sunday and Monday, Italy will hold a national referendum that could reduce the time required to apply for citizenship from 10 years to just five. This initiative is viewed as critical for those long-term residents who contribute to society but lack formal recognition. However, Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni and allies from her right-wing coalition have openly urged Italians to abstain from voting, claiming the current law is satisfactory.

The debate surrounding citizenship is inherently sensitive in Italy, a nation grappling with high numbers of migrants and refugees arriving from North Africa. Nevertheless, this referendum particularly targets individuals who have legally resided in Italy for employment, amidst a shrinking population. "This is about changing perceptions," says Carla Taibi from the liberal party More Europe. The reform would mainly affect those already established in the Italian workforce and their underage children.

Estimates suggest that about 1.4 million people may qualify for citizenship under the proposed changes. Improving this situation is critical for residents like Sonny, who struggle with the barriers non-citizens face when seeking public employment and even basic services. He recounts issues he faced while trying to participate in a reality TV show due to bureaucratic obstacles resulting from lacking citizenship.

Interestingly, despite its implications, the referendum has received scant attention from the media and a lack of organized opposition, raising concerns over the low turnout necessary for a valid vote. Experts like Professor Roberto D'Alimonte suggest that Meloni’s government strategically downplays the referendum's significance to prevent a majority turnout.

Meloni has publicly stated her intention to visit a polling station but abstain from voting, maintaining that citizenship laws are already quite progressive. Critics accuse her of undermining democratic participation with such tactics, with some coalition members claiming the referendum risks “erasing our identity.”

Age-old issues of racial and ethnic identity emerge as Sonny shares his belief that the struggles he faces in securing citizenship stem from racism. It serves as a poignant reminder of the complexity surrounding nationality in contemporary Italy. Activists like Insaf Dimassi, who describes her life as "Italian without citizenship," also articulate the frustration of feeling invisible. “Not being allowed to vote, or be represented, is being invisible,” Insaf remarks, stressing the need for recognition beyond mere meritocracy.

As the vote approaches, students in Rome have begun mobilizing, calling for the populace to support a "Yes" vote. Yet, with a government boycott and limited outreach, experts warn that meeting the turnout threshold may remain a challenge. Nonetheless, Sonny insists that regardless of the referendum's outcome, the fight for recognition and belonging continues: “Even if they vote ‘No’, we will stay here – and think about the next step.” This sentiment signals a growing resolve within communities advocating for a rightful place in Italy's social fabric.