Fears that South Sudan - the world's youngest nation - could plunge into a new civil war have intensified after the party of suspended Vice-President Riek Machar called for 'regime change'.

The call came after Machar - currently under house arrest - was charged with murder, treason and crimes against humanity.

His party, the Sudan People's Liberation Movement In Opposition (SPLM-IO), has denounced the charges as a 'political witch-hunt' to 'dismantle' a 2018 peace accord that ended a five-year civil war.

Meanwhile, extra troops from neighbouring Uganda have been deployed to South Sudan's capital, Juba, as tensions escalate.

The latest crisis comes as a UN report has accused South Sudanese officials of stealing billions of dollars in oil revenues, leaving millions of people without essential services and fuelling the deadly conflict.

What's the background?

South Sudan, one of the world's poorest countries, gained independence from Sudan in 2011 after decades of struggle led by the Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM) under President Salva Kiir.

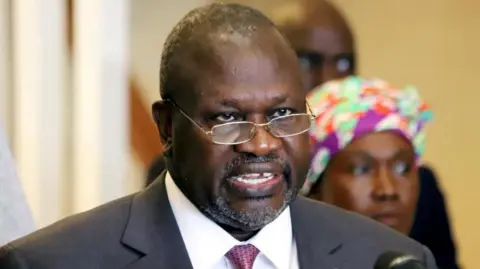

Just two years into independence, a civil war erupted when Kiir dismissed Machar as vice-president, accusing him of plotting a coup.

The ensuing conflict, largely fought along ethnic lines between supporters of the two leaders, resulted in an estimated 400,000 deaths and 2.5 million people being forced from their homes - more than a fifth of the population.

As part of the peace deal, Machar was reinstated as vice-president within a unity government that was meant to pave the way for elections.

Why is there tension now?

The current crisis was sparked at the beginning of March when the White Army militia, which was allied to Machar during the civil war, clashed with the army in Upper Nile state and overran a military base in Nasir.

Then on 7 March, a UN helicopter attempting to evacuate troops came under fire, leaving several dead, including a high-ranking army general.

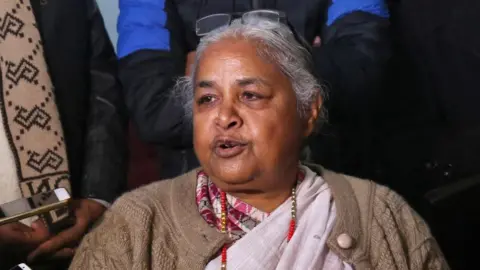

Nearly three weeks later, Machar and several of his associates were placed under house arrest. They were accused of trying to stir up a rebellion.

'The prospect for peace and stability in South Sudan has now been put into serious jeopardy,' Oyet Nathaniel Pierino, deputy leader of SPLM-IO, said at the time.

Rather than defusing tensions, the government struck again, hitting Machar with a slew of charges - including treason, the ultimate crime against the state - in September. Days later, his party ratcheted up the pressure, denouncing Kiir's government as a 'dictatorship' and demanding 'regime change'.

In what appeared to be a call to arms, it urged its supporters to 'report for national service' and to use 'all means available to regain their country and sovereignty'. However, there are no reports to suggest that troop mobilization is underway, offering a glimmer of hope that fresh fighting will not erupt.

What about the 2018 peace deal?

While Machar's inclusion in the unity government was a key part of the agreement, other parts of it have not been implemented. The key issue for many South Sudanese is the security arrangement.

The deal outlined how former rebel forces and government soldiers would be brought together into a unified national army made up of 83,000 troops. The remainder were supposed to be disarmed and demobilized. But this has not happened and there are still many militias aligned with different political groups. The deal also outlined the establishment, with the help of the African Union, of a court meant to try the perpetrators of the violence. But this has not been created, in part because those holding some top positions in government are reluctant to set up something that could see them put on trial.