The International Criminal Court (ICC) has opened its war crimes case against fugitive Ugandan rebel leader Joseph Kony in its first-ever confirmation of charges hearing without the accused present.

The proceedings mark a historic moment for the court and could serve as a test case for future prosecutions of high-profile suspects who currently appear to be beyond its reach.

Despite an arrest warrant issued 20 years ago, Kony, the founder and leader of the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA), has managed to evade arrest.

He faces 39 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity, including murder, sexual enslavement, abduction and forcing thousands of children to fight as soldiers in the LRA.

Kony said he wanted to install a government based on the biblical 10 commandments, and he was fighting for the rights of the Acholi people in northern Uganda. But his rebel group was notorious for hacking off their victims' limbs or parts of their faces.

Kony's notoriety increased in 2012 because of a social media campaign to highlight the LRA's alleged atrocities. Despite those efforts, and years of manhunts, he remains a fugitive.

There was silence in the courtroom as the catalogue of charges against him were read out. They also cover gender-based crimes linked to the treatment of thousands of women and girls, including their enslavement, rape, forced marriage and pregnancy.

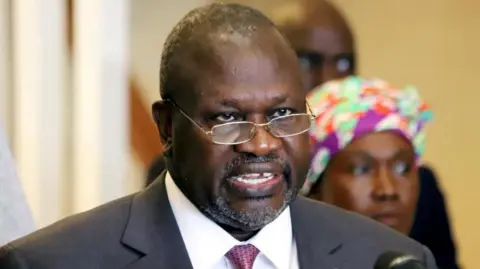

The atrocities were allegedly committed in northern Uganda between 2003 and 2004. Unfortunately the tentacles of international justice, even though they are lengthy, have not been sufficient to ensure the efficient arrest of fugitives, said the ICC's deputy prosecutor, Mame Mandiaye Niang.

According to the prosecution, children were regularly kidnapped on their way to school, from the fields, deprived of their fundamental rights, and forced to kill for Kony's rebel group.

For the first time, the ICC is exercising its power under the Rome Statute to move forward without a suspect in custody. Judges will hear the arguments of the prosecution, defence and representatives of victims. Kony will be represented in absentia by a court-appointed lawyer, before judges decide whether to confirm the charges.

A trial itself, however, cannot begin unless Kony is arrested and present in court in The Hague. Legal experts say the hearing could set a precedent for how the ICC handles other fugitives unlikely to be detained.

For survivors of the LRA's violence, the hearing is being watched closely, albeit remotely, on a big screen set up by ICC teams in northern Uganda. Rights advocates say it validates the suffering of thousands of people who endured the rebel group's reign of terror.

In the case of the LRA, the deputy prosecutor pointed out the scars cut through communities in which the victim became the perpetrator, but Kony, he said, remained the main perpetrator until the end. The LRA was forced out of Uganda by the army in 2005, and the rebels went into what was then Sudan and eventually set up camp in the border area with the Democratic Republic of Congo.

This underscores the ICC's determination to pursue accountability, even when arrests are difficult to achieve.