At Shona EPZ, a garment factory in Kenya's capital, Nairobi, the tension is inescapable. The industrious thrum of the heavy-duty sewing machines, along with the workers' chatter, normally fills the plant with a reassuring rhythm. But today every sound is tinged with uncertainty as the future of the firm is unclear because of the possible end of a key piece of US trade law.

The African Growth and Opportunity Act (Agoa), embedding in legislation a landmark trade agreement that has for 25 years given some African goods duty-free access to the US market, expires on Tuesday.

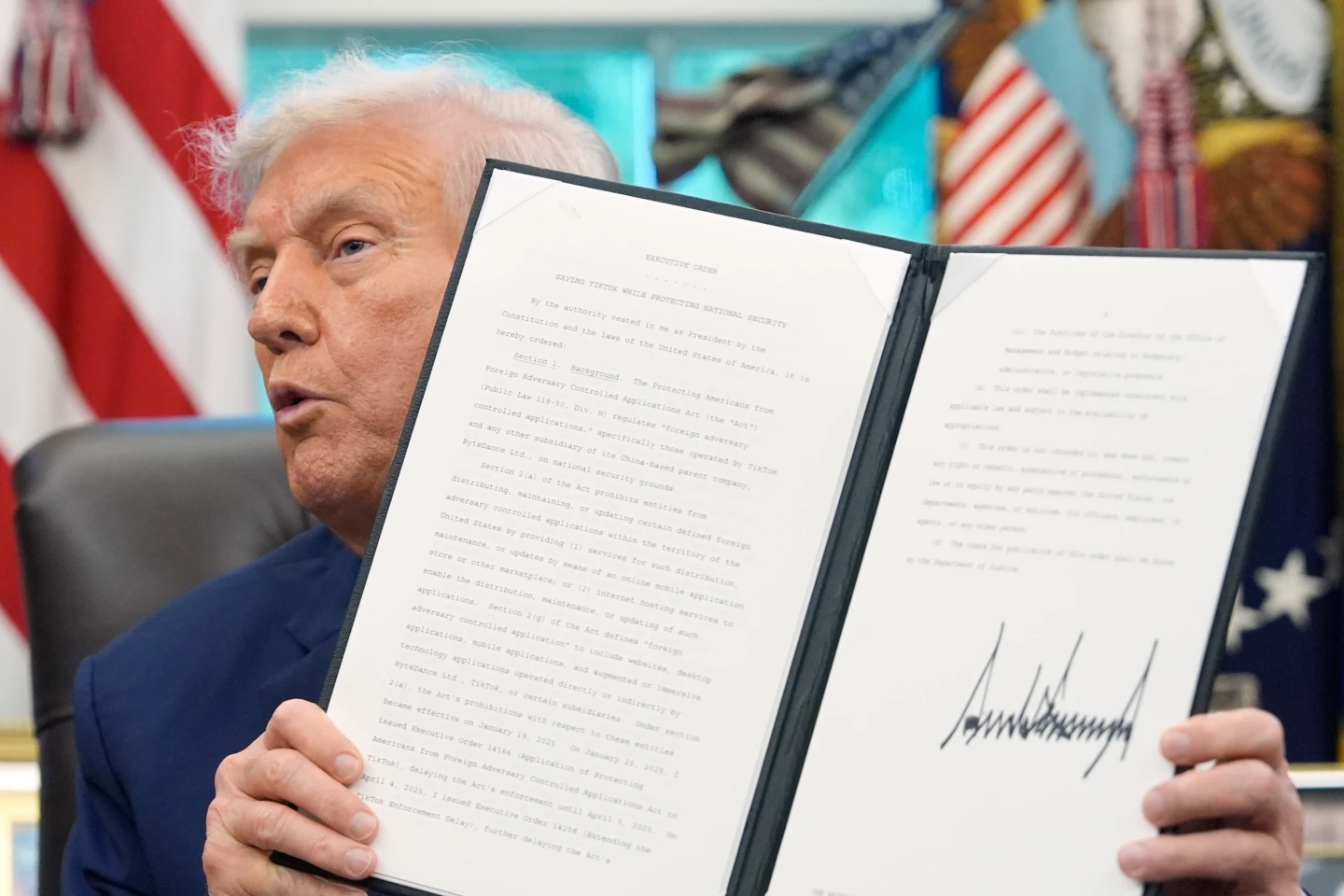

However, this policy is at odds with the Trump administration's record of imposing tariffs. Envoys from various African countries have gone to the US to try to negotiate an extension. A White House official told the BBC the administration supported a one-year extension to the programme, but this has not yet been announced.

Considered the cornerstone of US-Africa economic relations, Agoa's aim was to help industrialise the continent, create employment and lift dozens of countries out of poverty. It was based on a philosophy of replacing aid with trade.

Agoa has proved very valuable for countries such as Kenya and Lesotho and the fate of thousands of workers, like 29-year-old Joan Wambui, is tied up with its future. The end of the deal could spell the end of her job.

Ms. Wambui has worked at Shona EPZ, helping to sew sportswear exclusively for the American market, for just six months. In that short time, her salary has become the mainstay of her household. She supports her four-year-old daughter, two sisters in college, along with her mother.

If Agoa expires, where shall we go? Ms. Wambui asks in a worried tone, her hands and feet moving in time on the sewing machine as she stitches together pieces of fabric. For her, a regular wage has meant more than income; it has meant dignity and the ability to pay school fees, keep food on the table, and enabled her to look forward to a better future.

It's going to hit me hard. Starting to look for a new job. In Kenya, it's hard to find a job, very hard, she says as she folds the piece of fabric she has just stitched.

Kenya's apparel industry has thrived under Agoa. In 2024 alone, the country exported $470m worth of clothing to the US, supporting more than 66,000 direct jobs, three-quarters of them done by women, according to the Kenya Private Sector Alliance.

Factories like Shona EPZ have become important sources of employment, especially for young people who have struggled to find stable work in a tough economy.

The uncertainty stretches far beyond Kenya. Across Africa, more than 30 countries currently export over 6,000 products to the US under Agoa. The programme has been credited with creating jobs, boosting industries, and giving African economies a stronger foothold in global trade.

Kenya's Trade Minister Lee Kinyanjui revealed that Nairobi was pushing for at least a short extension. An ideal situation would be the extension of Agoa so transition mechanisms can be put in place, he said. As the clock ticks down toward the expiration date, the pressure to secure a deal grows ever more urgent.

The African Growth and Opportunity Act (Agoa), embedding in legislation a landmark trade agreement that has for 25 years given some African goods duty-free access to the US market, expires on Tuesday.

However, this policy is at odds with the Trump administration's record of imposing tariffs. Envoys from various African countries have gone to the US to try to negotiate an extension. A White House official told the BBC the administration supported a one-year extension to the programme, but this has not yet been announced.

Considered the cornerstone of US-Africa economic relations, Agoa's aim was to help industrialise the continent, create employment and lift dozens of countries out of poverty. It was based on a philosophy of replacing aid with trade.

Agoa has proved very valuable for countries such as Kenya and Lesotho and the fate of thousands of workers, like 29-year-old Joan Wambui, is tied up with its future. The end of the deal could spell the end of her job.

Ms. Wambui has worked at Shona EPZ, helping to sew sportswear exclusively for the American market, for just six months. In that short time, her salary has become the mainstay of her household. She supports her four-year-old daughter, two sisters in college, along with her mother.

If Agoa expires, where shall we go? Ms. Wambui asks in a worried tone, her hands and feet moving in time on the sewing machine as she stitches together pieces of fabric. For her, a regular wage has meant more than income; it has meant dignity and the ability to pay school fees, keep food on the table, and enabled her to look forward to a better future.

It's going to hit me hard. Starting to look for a new job. In Kenya, it's hard to find a job, very hard, she says as she folds the piece of fabric she has just stitched.

Kenya's apparel industry has thrived under Agoa. In 2024 alone, the country exported $470m worth of clothing to the US, supporting more than 66,000 direct jobs, three-quarters of them done by women, according to the Kenya Private Sector Alliance.

Factories like Shona EPZ have become important sources of employment, especially for young people who have struggled to find stable work in a tough economy.

The uncertainty stretches far beyond Kenya. Across Africa, more than 30 countries currently export over 6,000 products to the US under Agoa. The programme has been credited with creating jobs, boosting industries, and giving African economies a stronger foothold in global trade.

Kenya's Trade Minister Lee Kinyanjui revealed that Nairobi was pushing for at least a short extension. An ideal situation would be the extension of Agoa so transition mechanisms can be put in place, he said. As the clock ticks down toward the expiration date, the pressure to secure a deal grows ever more urgent.