As the war in Gaza grinds on, Israel's international isolation appears to be deepening.

Is it approaching a South Africa moment, when a combination of political pressure, economic, sporting and cultural boycotts helped to force Pretoria to abandon apartheid?

Or can the right-wing government of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu weather the diplomatic storm, leaving Israel free to pursue its goals in Gaza and the occupied West Bank without causing permanent damage to its international standing?

Two former prime ministers, Ehud Barak and Ehud Olmert, have already accused Netanyahu of turning Israel into an international pariah.

Thanks to a warrant issued by the International Criminal Court, the number of countries Netanyahu can travel to without the risk of being arrested has shrunk dramatically.

At the UN, several countries, including Britain, France, Australia, Belgium and Canada, have said they are planning to recognise Palestine as a state next week.

And Gulf countries, reacting with fury to last Tuesday's Israeli attack on Hamas leaders in Qatar, have been meeting in Doha to discuss a unified response, with some calling on countries which enjoy relations with Israel to think again.

But with images of starvation emerging from Gaza over the summer and the Israeli army poised to invade - and quite possibly destroy - Gaza City, more and more European governments are showing their displeasure in ways that go beyond mere statements.

At the start of the month, Belgium announced a series of sanctions, including a ban on imports from illegal Jewish settlements in the West Bank, a review of procurement policies with Israeli companies and restrictions on consular assistance to Belgians living in settlements.

It also declared two hardline Israeli government ministers, Itamar Ben-Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich, persona non grata, along with Jewish settlers accused of violence against Palestinians in the West Bank.

Other countries, including Britain and France, had already taken similar steps. But sanctions on violent settlers imposed by the Biden administration last year were scrapped on Donald Trump's first day back in the White House.

A week after Belgium's move, Spain announced its own measures, turning an existing de facto arms embargo into law, announcing a partial import ban, barring entry to Spanish territory for anyone involved in genocide or war crimes in Gaza, and prohibiting Israel-bound ships and aircraft carrying weapons from docking at Spanish ports or entering its airspace.

Israel's combative foreign minister, Gideon Saar, accused Spain of advancing antisemitic policies and suggested that Spain would suffer more than Israel from the arms trade ban.

But there are other alarming signs for Israel.

In August, Norway's vast $2tn sovereign wealth fund announced it would start divesting from companies listed in Israel. By the middle of the month, 23 companies had been removed and finance minister Jens Stoltenberg said more could follow.

Meanwhile, the EU, Israel's largest trading partner, plans to sanction far-right ministers and partly suspend trade elements of its association agreement with Israel.

In her 10 September State of the Union speech, EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said events in Gaza had shaken the conscience of the world.

A day later, 314 former European diplomats and officials wrote to von der Leyen and EU foreign policy chief Kaja Kallas calling for tougher measures, including a full suspension of the association agreement.

One feature of the sanctions levelled at South Africa between the 1960s and the end of apartheid in the 1990s was a series of cultural and sporting boycotts.

Again, there are signs of this starting to happen with Israel.

The Eurovision Song Contest might not sound like a significant event in this context, but Israel has a long and illustrious history with the competition, winning it four times since 1973.

For Israel, participation is symbolic of the Jewish state's acceptance among the family of nations.

But Ireland, Spain, the Netherlands and Slovenia have all said, or hinted, that they will withdraw in 2026 if Israel is allowed to compete, with a decision expected in December.

In Hollywood, a letter calling for a boycott of Israeli production companies, festivals and broadcasters that are implicated in genocide and apartheid against the Palestinian people has attracted more than 4,000 signatures in a week, including household names like Emma Stone and Javier Bardem.

Tzvika Gottlieb, CEO of the Israeli Film and TV Producers Association, called the petition profoundly misguided.

Then there is sport. The Vuelta de Espana cycling race was repeatedly disrupted by groups protesting the presence of the Israel-Premier Tech team, forcing a messy, premature end and the cancellation of the podium ceremony.

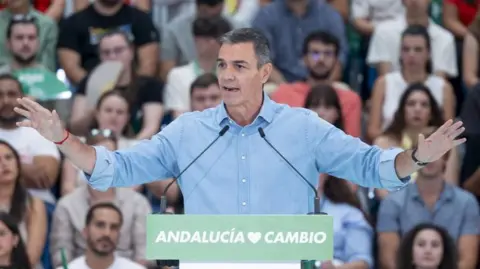

Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez called the protests a source of pride, but opposition politicians said government actions had caused international embarrassment.

But among those who have represented Israel abroad, there is deep anxiety.

Jeremy Issacharoff, Israel's ambassador to Germany from 2017 to 2021, told me he could not recall Israel's international standing being so impaired, but said many of the moves were regrettable as they were inevitably being seen as targeting all Israelis.

Despite his fears, the former ambassador does not believe Israel's diplomatic isolation is irreversible.

We're not in a South African moment, but we're in a possible preamble to a South African moment, he said.

Baruch expressed that recent sanctions were necessary: That's how South Africa was pushed to its knees.

Daniel Levy, a former Israeli peace negotiator, explained that many are skeptical about the potential for unified action against Israel, given the resistance from other EU member states like Germany and Italy.